Original title: The Untold Story of a Crypto Crimefighters Descent Into Nigerian Prison

Original author: Andy Greenberg, Wired

Compiled by: Tracy, Alvin, compare BitpushNews

As a U.S. federal agent, Tigran Gambaryan pioneered modern cryptocurrency investigations. Later at Binance, he fell between the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange and a government determined to make it pay.

At 8 a.m. on March 23, 2024, Tigran Gambaryan woke up on the sofa in Abuja, Nigeria, where he had been dozing off since pre-dawn prayers. The houses around him, often accompanied by the buzzing of nearby generators, are now unusually quiet. In that silence, the harsh reality of Gambaryan’s situation flooded into his mind every morning for nearly a month: He and his colleague Nadeem Anjarwalla at the cryptocurrency company Binance were taken hostage and were unable to obtain their passport. They were detained under military guards in a compound fenced by barbed wire owned by the government of Nigeria.

Gambaryan stood up from the sofa. Wearing a white T-shirt, the 39-year-old Armenian American is strong and muscular, and has Orthodox tattoos all over his right arm. He usually shaved his head, but his neatly trimmed black beard has become short and messy since he hadn’t shaved for a month. Gambaryan approached the chef in the compound and asked if she could buy him some cigarettes. He then walked into the interior courtyard of the house and began to walk around restlessly, calling his lawyer and other Binance contacts to resume his daily effort, in his words, to “fucking solve this problem.”

Just the day before, the two Binance employees and their cryptocurrency giant employer were told they were about to be charged with tax evasion. The two men appear caught in the middle of a bureaucratic conflict between an irresponsible foreign government and one of the most controversial players in the cryptocurrency economy. Now, they are not only being held forcibly, but with no end in sight, and accused of being criminals.

Gambaryan spoke on the phone for more than two hours, and the courtyard began to be roasted by the rising sun. When he finally hung up the phone and returned to the house, he still didn’t see any trace of Anjarwalla. Before dawn that morning, Anjarwalla went to the local mosque to pray, and the wardens accompanying him kept him under strict supervision. When Anjarwalla returned to the house, he told Gambaryan that he was going back upstairs to sleep.

Hours had passed since then, so Gambaryan went up to his second-floor bedroom to visit his colleagues. He pushed open the door and found that Anjarwalla seemed to be asleep, his feet sticking out from under the sheets. Gambaryan called to him at the door, but received no response. For a moment, he feared that Anjarwalla might have another panic attack-the young British-born Kenyan Binance executive had been sleeping in Gambaryan’s bed for days and was too anxious to spend the night alone.

Gambaryan walked through the dark room-he heard that the house’s government caretakers were delinquent on electricity bills and the generator was short of diesel, so all-day power outages were common-and put his hand on the blanket. Strangely enough, the blanket sank as if there were no real human bodies underneath.

Gambaryan pulled open the sheet. He found a T-shirt underneath with a pillow stuffed inside. He looked down at his foot sticking out of the blanket and now realized that it was actually a sock with a water bottle inside.

Gambaryan no longer called Anjarwalla and did not search the house. He already knew that his Binance colleagues and fellow inmates had escaped. He also immediately realized that his situation would get worse. He doesn’t yet know it will get worse-he will be sent to a Nigeria prison, charged with money laundering, punishable by 20 years in prison, without access to medical care even if his health deteriorates to the point of death, and being used as a pawn in a multibillion-dollar cryptocurrency extortion scheme.

At that moment, he just sat silently in bed, thinking about the fact that he was now completely alone in the darkness of 6,000 miles from home.

TIGRAN GAMBARYAN’s growing nightmare in Nigeria stems at least in part from a 15-year conflict. Since the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto revealed Bitcoin to the world in 2009, cryptocurrency has promised a holy grail of liberalism: a digital currency that is not controlled by any government, is unaffected by inflation, and can travel across national borders unscrupulously as if it existed in a completely different dimension. However, the reality today is that cryptocurrency has become a trillion-dollar industry, largely run by companies with gorgeous offices and high-paying executives-countries where legal and law enforcement agencies are able to put pressure on cryptocurrency companies and their employees just as they do on any other real-world industry.

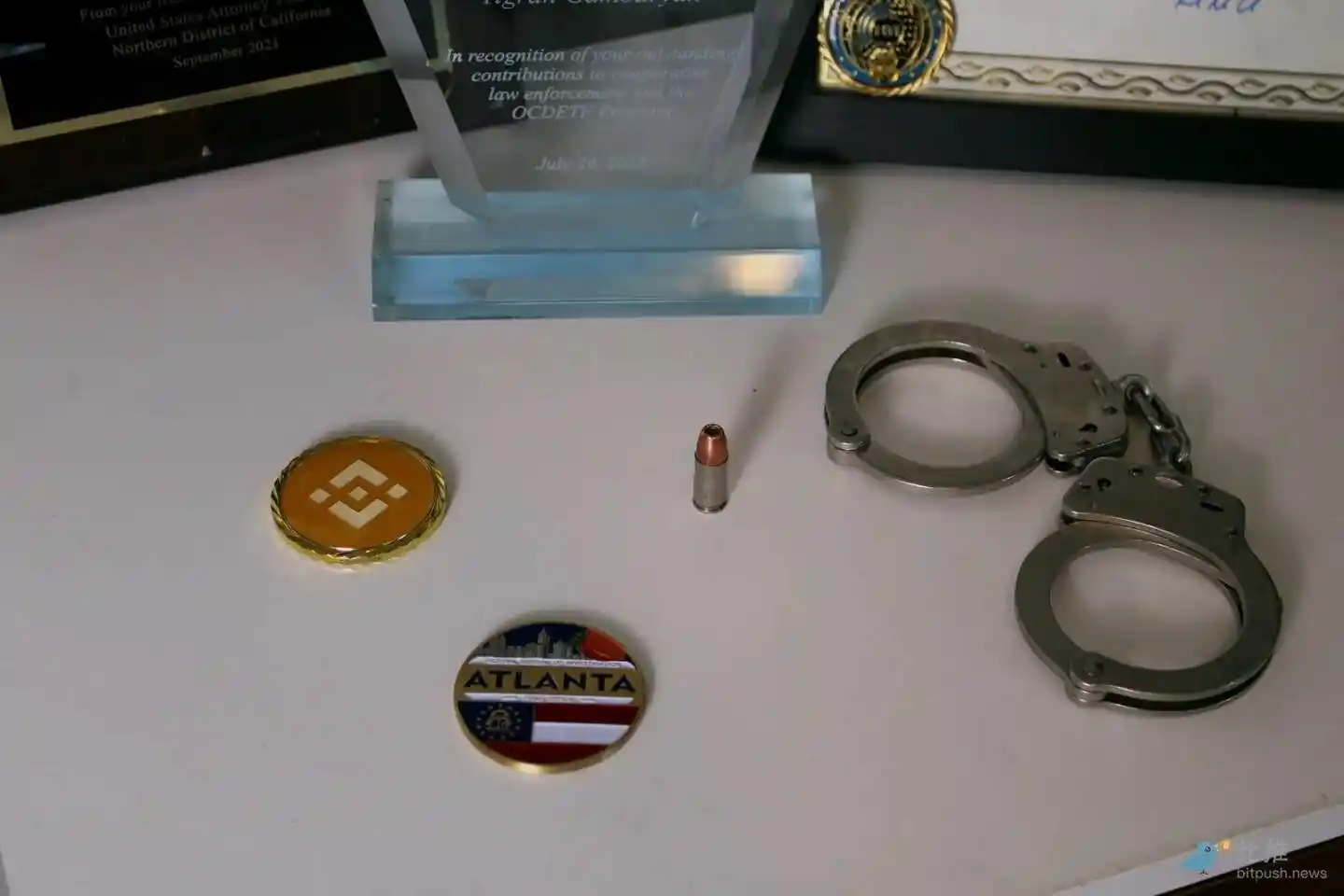

Before becoming one of the world’s most well-known victims and falling victim to the conflict between disorderly fintech and global law enforcement, Gambaryan embodied the conflict in another way: as one of the world’s most effective and innovative full-time cryptocurrency law enforcement officers. For ten years before joining Binance in 2021, Gambaryan served as a special agent for the Internal Revenue Service’s Bureau of Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI), responsible for performing law enforcement work with tax agencies. During his tenure at IRS-CI, Gambaryan pioneered technology to track cryptocurrencies and identify suspects by parsing the Bitcoin blockchain. With this “tracking funds” tactic, he destroyed one cybercrime conspiracy after another and completely subverted the myth of Bitcoin’s anonymity.

Starting in 2014, after the FBI seized the Silk Road dark-net drug market, it was Gambaryan who tracked Bitcoin and exposed two corrupt federal agents who stole more than $1 million while investigating the market-the first time blockchain evidence has been included in a criminal indictment. Over the next few years, Gambaryan helped track records from Mt. Gox’s theft of $500 million worth of Bitcoin ultimately confirmed that a group of Russian hackers were behind the theft.

In 2017, Gambaryan partnered with blockchain analytics startup Chainalysis to create a secret bitcoin tracking method that successfully found and helped the FBI seize the server hosting AlphaBay. AlphaBay is a dark web criminal market estimated to be 10 times the size of the Silk Road. A few months later, Gambaryan played a key role in destroying the cryptocurrency-funded child sexual abuse video network Welcome to Video, the largest market of its kind to date. The operation resulted in the arrest of 337 users around the world and the rescue of 23 children.

Eventually, in 2020, Gambaryan and another IRS-CI agent tracked down and seized nearly 70,000 bitcoins that had been stolen from the Silk Road years ago by a hacker. At today’s prices, these bitcoins are worth $7 billion, making them the largest criminal confiscation of any currency type in history, flowing into the U.S. Treasury Department.

“The cases he was involved in covered almost all the largest cryptocurrency cases at the time,” said Will Frentzen, a former U.S. prosecutor who worked closely with Gambaryan and prosecuted the crimes Gambaryan exposed. “He was very innovative in his investigations, used methods that many people had not imagined, and was also very selfless in his treatment of receiving honors.” In his battle against cryptocurrency crime, Frentzen said: “I don’t think anyone has had a greater impact on this field than he.”

After that storied career, Gambaryan turned to the private sector and made a decision that shocked many of his government colleagues who had worked with him. He became the head of Binance’s investigation team. Binance is a huge cryptocurrency exchange that handles tens of billions of dollars in daily transactions and is known for being indifferent to whether users violate the law.

When Gambaryan joined Binance in the fall of 2021, the company was already the subject of an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice. In the end, the investigation showed Binance processed billions of dollars in transactions that violated anti-money laundering laws and circumvented international sanctions on Iran, Cuba, Syria and Russian-occupied Ukraine. The Justice Department also pointed out that the company directly processed more than $100 million in cryptocurrency transactions from the Russian dark-web criminal market Hydra, even from sources in some cases including the sale of child sexual abuse material and funding of identified terrorist organizations.

Some of Gambaryan’s old colleagues privately expressed dissatisfaction with his career change and even believed that he “sold himself to the enemy.” However, Gambaryan firmly believes that he is actually taking on the most important role in his career. As part of Binance’s efforts to clean up the company’s image after years of rapid expansion, Gambaryan formed a new investigative team within the company. He recruited many top agents from IRS-CI and other law enforcement agencies around the world and helped Binance develop unprecedented cooperation with law enforcement agencies.

Gambaryan said that by analyzing data with trading volumes exceeding the New York Stock Exchange, London Stock Exchange and Tokyo Stock Exchange combined, his team has successfully helped crack cases of child sexual abuse, terrorists and organized crime around the world. “We have assisted in thousands of cases around the world. My influence at Binance may be even greater than when I was in law enforcement,”Gambaryan once told me.” I am very proud of the work we have done, and I am always willing to debate if anyone questions my decision to join Binance.

Although Gambaryan has helped Binance create a more law-abiding image, the shift will not erase the company’s history as an illegal exchange or protect it from the consequences of past criminal behavior. In November 2023, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland announced at a press conference that Binance had agreed to pay $4.3 billion in fines and forfeiture, one of the largest corporate penalties in U.S. criminal justice history. Company founder and CEO Zhao Changpeng was personally fined US$150 million and sentenced to four months in prison.

The United States is not the only country dissatisfied with Binance. By early 2024, Nigeria also began to accuse the company, not only for compliance violations it admitted in the U.S. plea agreement, but also because Binance was accused of exacerbating the devaluation of Nigeria’s currency, the naira. From the end of 2023 to the beginning of 2024, the naira has depreciated by nearly 70%, and Nigeria people have exchanged their currencies for cryptocurrencies, especially the “stablecoins” pegged to the US dollar.

Amaka Anku, head of Africa at Eurasia Group, said that the real reason for the devaluation of the naira was that the government of Nigeria’s new President Bola Tinubu relaxed the exchange rate restrictions between the naira and the US dollar, and the Central Bank of Nigeria’s foreign exchange reserves were unexpectedly small. However, when the naira began to devalue, cryptocurrencies used it as an unregulated way to sell naira, further exacerbating the devaluation pressure. “You can’t say that Binance or any crypto exchange directly contributed to this devaluation,” Anku said,”but they do exacerbate the process.”

For years, proponents of cryptocurrencies have imagined that Satoshi’s invention would provide a safe haven for citizens of countries facing an inflation crisis. The moment has finally arrived, and the government of Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, is furious. In December 2023, a committee of the Nigeria Parliament asked top officials of Binance to attend a hearing in the capital Abuja to explain how they corrected the alleged mistakes. In response to the situation, Binance convened a Nigeria delegation, and Tigran Gambaryan, a former federal agent and star investigator, naturally became a member of the delegation as a symbol of the company’s commitment to working with law enforcement agencies and governments around the world.

However, before resorting to extreme methods such as coercion and hostage kidnapping,(the perpetrator) first made demands for bribes.

In January 2023, Gambaryan had only arrived in Abuja for a few days and his journey went smoothly. As a gesture of goodwill, he met with investigators from the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) of Nigeria. The EFCC is basically Gambaryan’s counterpart when he worked for the IRS, responsible for tasks such as combating fraud and investigating government corruption, and discussed the possibility of providing training for the agency’s employees in cryptocurrency investigations. He then attended a roundtable meeting with Binance executives and members of the Nigeria House of Representatives, who promised each other in a cordial atmosphere and would work together to resolve differences.

When Gambaryan arrived in Nigeria, it was EFCC detective Olalekan Ogunjobi who received him at the airport. Ogunjobi has read Gambaryan’s professional experience and expressed great admiration for his legendary achievements as a federal agent. Throughout the trip, Ogunjobi had dinner with Gambaryan almost every night at the hotel, the Transcorp Hilton Abuja. Gambaryan and Ogunjobi shared their experience in crypto-crime investigations, how to handle cases, and how to form a task force. They exchanged a lot of investigative experience. When Gambaryan presented his book “Tracers in the Dark” to Ogunjobi and signed it, Ogunjobi asked him to sign it.

One night, while Gambaryan and Ogunjobi and a group of Binance colleagues were dining at the table, a Binance employee received a call from the company’s lawyer. After the pleasantries, the lawyer told Gambaryan that the meeting with Nigeria officials was actually not as friendly as it seemed. Officials are now demanding a payment of US$150 million to address Binance’s problems in Nigeria-and demanding that payments be made in cryptocurrency, directly into officials ‘cryptowallets. Even more shocking, officials suggested that Binance’s team would not be able to leave Nigeria until the money was in place.

Gambaryan was so shocked that he didn’t even have time to explain or bid farewell to Ogunjobi. He hurriedly packed up Binance’s employees, hurriedly left the restaurant, and returned to the conference room of the Transcorp Hilton Hotel to discuss the next step. Paying the obvious bribe would violate the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. If they refuse, they could be detained indefinitely. In the end, the team decided to take the third option: leave Nigeria immediately. They spent the night in the conference room urgently planning how to get all Binance employees to board the plane as soon as possible, change flights, and advance their departure time to the next morning.

The next morning, the Binance team gathered on the second floor of the hotel, their luggage had been packed, and they tried to avoid passing through the lobby in case Nigeria officials might be waiting for them in the lobby and prevent them from leaving. Everyone took a taxi to the airport, nervously passed the security check, and successfully boarded the plane and returned home. No problems occurred during the whole process. Everyone felt as if they had escaped a disaster.

Shortly after returning to suburban Atlanta, Gambaryan received a call from Ogunjobi. Gambaryan said that Ogunjobi was very disappointed that Binance’s team had received bribes and was shocked by the behavior of his fellow Nigeria. Ogunjobi suggested that Gambaryan report the bribery incident to the Nigeria authorities and ask them to launch an anti-corruption investigation.

Eventually, Ogunjobi arranged a phone call between Gambaryan and EFCC official Ahmad Sa ‘ad Abubakar. Abubakar was introduced as a right-hand man to Nigeria’s national security adviser Nuhu Ribadu. Ogunjobi told Gambaryan that Ribadu is an anti-corruption fighter and has even given a speech on TEDx. Now, Ribadu has invited Gambaryan to meet with him in person to resolve Binance’s problems in Nigeria and thoroughly investigate the truth about the bribery incident.

Gambaryan told his Binance colleagues about the phone call, which sounded like an opportunity to resolve the company’s woes in Nigeria. So Binance executives and Gambaryan began to think that maybe he could use the invitation to return to Nigeria and untangle the company’s increasingly complex relationship with the Nigeria government. Although the idea may sound risky-after all, they had just fled the country in a hurry a few weeks ago-Gambaryan believes he received a friendly invitation from a powerful official and received personal assurances from his friend Ogunjobi. Binance local staff also told Gambaryan that they had verified the solution and believed it was reliable.

Gambaryan told his wife Yuki about the bribery and the invitation to return to Nigeria. For her, this proposal is obviously very dangerous. She repeatedly asked Gambaryan not to go.

Gambaryan now admits that perhaps he still retained the way of thinking as a U.S. federal agent-an identity with a sense of responsibility and security. “I think that’s the part that was left behind: when duty calls, you do it,” he said. “I was asked to go.”

So, in what he now considers one of the most unwise decisions of his life, Gambaryan packed his bags, kissed Yuki and his two children, and set off in the early morning of February 25 to catch a flight to Abuja.

The second trip began with the airport pick-up at Ogunjobi. Ogunjobi once again assured him that he would comfort him repeatedly while driving to the Transcorp Hilton Hotel and at dinner. This time, Gambaryan was accompanied by Binance East Africa regional manager Nadeem Anjarwalla, a British Kenyan recent graduate of Stanford University who had a baby at home in Nairobi.

However, when Gambaryan and Anjarwalla walked into a meeting with Nigeria officials the next day, they were surprised to find Abubakar was attending with staff from the EFCC and Central Bank of Nigeria. Soon, the focus of the meeting became clear: the meeting was not about corruption in Nigeria. At the beginning of the meeting, Abubakar asked about Binance’s cooperation with Nigeria law enforcement agencies, and then turned the topic to the EFCC’s request to obtain transaction data from Binance’s Nigeria users. Abubakar said Binance only provided data for the past year, not all the data he requested. Gambaryan felt he had been raided, explaining that it was an oversight caused by a temporary request and promising to provide all needed data as soon as possible. Although Abubakar appeared dissatisfied, the meeting continued and finally everyone exchanged business cards in a friendly manner.

Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were left in the corridor waiting for their next appointment. After a while, Anjarwalla went to the bathroom. When he returned, he said he heard angry voices from some officials he had just met from a nearby conference room, which Gambaryan remembered saying.

After waiting for nearly two hours, Ogunjobi returned and led them into another conference room. Gambaryan remembered that the officials in this conference room looked solemn and the atmosphere was extremely serious. Everyone sat silently, as if waiting for someone to arrive-Gambaryan didn’t know who that person was. He noticed the shocked expression on Ogunjobi’s face and did not dare to look him in the eye. “What happened?” He thought to himself.

At this time, a middle-aged man named Hamma Adama Bello entered the room. He was an EFCC official, wearing a gray suit and a shaved beard, and looked to be in his forties. Without saying hello or asking questions, he placed a folder on the table and immediately began to scold, which Gambaryan remembered saying: Binance was “destroying our economy” and financing terrorism.

He then told Gambaryan and Anjarwalla what would happen: They would be taken back to the hotel to pack their bags and then moved to another location, where there would be more EFCC officials and a few central bank personnel, until Binance handed over all transaction data involving every Nigeria who had ever used the platform.

Gambaryan felt his heart racing. He immediately stated that he did not have the authority and could not provide such a large amount of data-the purpose of his trip was actually to report the bribery to Bello’s agency.

Bello seemed a little surprised when he heard about the bribery, as if it was the first time he had heard of such a thing, but soon ignored it. The meeting is over. Gambaryan quickly sent a text message to Noah Perlman, Binance’s chief compliance officer, telling him they could be detained. Officials then took their mobile phones.

The two were taken outside to a black Rand cruiser with dark window film on the windows. The SUV took them back to the Transcorp Hilton Hotel and took them back to their rooms-Anjarwalla followed Bello and another official, and Gambaryan led by Ogunjobi. They were told to pack their luggage. Gambaryan remembers saying to Ogunjobi,”You know how bad this is?”

Ogunjobi hardly dared to look him in the eye and replied,”I know, I know.”

The Land Cruiser then took them to a large two-story house in a walled compound with marble floors, big enough to accommodate two Binance employees and several EFCC officials in the bedroom, as well as a personal chef. Gambaryan later learned that the house was the government-designated residence of national security adviser Ribadu, but Ribadu chose to live in his own home and left the place for official use-in this case, as a temporary detention place for them.

That night, Bello made no further requests. Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were told they could rest after eating a Nigeria stew made by the chef in the house. Gambaryan lay in bed, anxious and almost panicked because he had no mobile phone, could not contact the outside world, or even tell his family where he was.

It was not until two o’clock in the morning that he finally fell asleep, and a few hours later, he woke up amid the early morning prayers of Muesin. Too anxious to stay in bed, he walked into the yard of the house, smoked a cigarette and thought about his current predicament: he was a hostage, caught in the financial crime he had devoted his life to fighting.

But in addition to this sense of irony, what overwhelmed him even more was the sense of complete unknown. “What will happen to me? What will Yuki go through?” He thought of his wife and was filled with anxiety. “How long will we stay here?”

Gambaryan stood in the yard smoking until the sun rose.

The trial followed.

Breakfast was prepared by the chef, but Gambaryan had no appetite for it. Bello sat down with them and told them that to release them, Binance had to hand over all data on Nigeria users and ban peer-to-peer transactions by Nigeria users. Peer-to-peer trading is a feature on the Binance platform that allows traders to advertise the sale of cryptocurrencies based on exchange rates they partially control, which Nigeria officials believe has contributed to the devaluation of the naira.

In addition to these requirements, there was an unspecified request in the conference room: Binance would have to make a huge payment. When Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were detained, Nigeria communicated with Binance executives through secret channels and the company learned that they were demanding billions of dollars. According to people involved in the negotiations, government officials even publicly told the BBC that the fine would reach at least US$10 billion, more than double the highest settlement amount Binance paid to the United States in history. (Binance did propose “deposit” plans based on the company’s tax liability in Nigeria, according to several people familiar with the matter, but these proposals were never accepted. Meanwhile, the day after Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were detained, the U.S. Embassy received a strange letter from the EFCC stating that Gambaryan had been detained “solely for constructive dialogue” and “voluntarily participated in these strategic dialogues.”

Gambaryan repeatedly explained to Bello that he had no actual power in Binance’s business decisions and was unable to meet his demands. Bello did not change his tone after hearing this and continued to accuse Binance at length of the damage caused to Nigeria and claimed that Nigeria should be compensated. Gambaryan recalled that Bello sometimes showed off the guns he carried and showed photos of himself training in Quantico, Virginia, in cooperation with the FBI, seemingly showing his authority and connection to the United States.

Ogunjobi also participated in the interrogation. Gambaryan said he was quieter and more respectful than Bello, but he was no longer the respectful student. When Gambaryan mentioned that he had provided a lot of help to law enforcement in Nigeria, Ogunjobi responded that he had read comments on LinkedIn that Binance had hired him only to create the illusion of legitimacy, which shocked Gambaryan, especially after their long previous conversation.

Angry and unable to meet Nigeria’s demands, Gambaryan asked to see a lawyer, contact the U.S. Embassy and return his mobile phone, but all requests were denied, although he was allowed to call his wife in the presence of guards.

Amid a standoff with EFCC officials, Gambaryan told them he would not eat unless he was allowed to see lawyers and contact the embassy. He began a hunger strike and was trapped in this house, guarded by government personnel and guards, sitting on the sofa and watching Nigeria TV all day long. After five days of hunger strike, officials finally gave in.

He and Anjarwalla were returned their mobile phones, but were told not to contact the media and their passports were withheld. They were then allowed to meet with local lawyers hired by Binance. After a week of detention, Gambaryan was taken to the Nigeria government building to meet with local diplomats. Diplomats said they would pay attention to Gambaryan’s situation, but so far there has been no way to set him free.

Then they began to live a daily life like Groundhog Day, circling around as Gambaryan later told his wife. The house was spacious and clean, but dilapidated, with a leaking roof and no electricity for many days. Gambaryan befriended the chef and some caretakers and watched the pirated series of “The Avatar: The Last Airbender” with them. Anjarwalla began doing yoga every day and drinking the smoothies made for him by the chef.

Anjarwalla seemed more overwhelmed by the anxiety of their captivity than Gambaryan, who was frustrated by missing his son’s first birthday. Nigeria withheld his British passport, but they did not realize that Anjarwalla also held his Kenyan passport. He joked with Gambaryan about running away, but Gambaryan said he never seriously thought about it. He told himself that Yuki had told him to “don’t do stupid things” and that he had no intention of taking risks.

One day, Anjarwalla lay on the sofa and told Gambaryan that he felt uncomfortable and was cold. Gambaryan covered him with many blankets, but he was still shaking. In the end, Nigeria took Anjarwalla and Gambaryan to the hospital and took another black Land Cruiser to test Anjarwalla for malaria. The test came back negative, and the doctor told Anjarwalla that he was actually having a panic attack. Every night since then, Gambaryan said, Anjarwalla would sleep next to him because he was too afraid to sleep alone.

In the second week of Gambaryan and Anjarwalla’s imprisonment, Binance agreed to the request, shut down its peer-to-peer trading feature in Nigeria and canceled all Naira transactions. EFCC officials told Gambaryan and Anjarwalla to be ready to pack their bags and release them. The two were very serious after hearing the good news. Gambaryan even used his mobile phone to take a video of the house as a commemoration of this strange life.

However, before they were about to be released, government caretakers took them to the EFCC office. The agency’s chairman asked for confirmation whether Binance had handed over all data on users in Nigeria. When he learned that Binance had not provided it, he immediately revoked the release decision and sent the two men back to the hotel.

At this time, the first thing was that cryptocurrency website DLNews reported that two Binance executives were detained in Nigeria, although they did not disclose their names. A few days later, the Wall Street Journal and Wired also confirmed that the detainees were Anjarwalla and Gambaryan.

Bello was angry about the news leak, and Gambaryan recalled that Bello blamed him and Anjarwalla. Bello told them that if they hand over the data required by the government, they would be free. Gambaryan lost patience and asked Bello,”Do you want me to take it out of my right pocket or out of my left pocket?” He recalled standing up and exaggeratedly pulling something out of one pocket and then out of the other. “I simply have no way to provide this data.”

Weeks have passed, but there is still no progress in the negotiations. Ramadan began, and Gambaryan would get up with Anjarwalla to pray every morning, and fast with him during the day to show friendly unity.

However, after nearly a month of hardship, things suddenly changed. One morning, Gambaryan woke up and saw that Anjarwalla had returned from the mosque. When he went to find his companions, he found that only a shirt stuffed into a pillow and a water bottle in his socks remained on the bed-Anjarwalla had escaped.

Gambaryan later learned that Anjarwalla had managed to escape Nigeria on a flight. He speculated that Anjarwalla might have somehow jumped over the yard wall, managed to avoid the guards-who often slept in the morning-and then paid for a taxi to the airport, before finally boarding the plane with his second passport.

Gambaryan has realized that his situation in Nigeria is about to undergo drastic changes. He walked into the yard and recorded a selfie video to send to his wife Yuki and Binance’s colleagues, talking into the camera as he walked.

“I have been detained by the Nigeria government for a month and I don’t know what will happen after today.” He said calmly and controlled. “I didn’t do anything wrong. I’ve been a cop my whole life. I only asked the Nigeria government to let me go, and I also asked the U.S. government to provide help. I need your help, everyone. I don’t know if I could get away without your help. Please help me.”

When Nigeria learned that Anjarwalla had escaped, guards and wardens took Gambaryan’s mobile phone and began a crazy search of the house. Soon, they disappeared and replaced with new people.

Presuming that something more serious might happen next, Gambaryan managed to persuade a Nigeria to quietly lend him his mobile phone, then went to the bathroom to call his wife, and contacted Yuki late at night. Gambaryan said it was the first time in their 17-year relationship that he had told her he was afraid. Yuki cried, and she went into the closet to talk to him to avoid waking the child. Then Gambaryan suddenly hung up the phone-someone was coming.

A military official told Gambaryan to pack his bags and said he would be released. Although he knew this could not be true, he still packed his things, walked into the car outside, and saw Ogunjobi sitting in the car. When Gambaryan asked Ogunjobi where they were going, Ogunjobi answered vaguely that maybe he was going home, but not today-and then looked at his phone silently.

The car eventually drove into the EFCC compound, rather than parked near the headquarters, but drove directly to the detention facility. Gambaryan scolded the guards angrily, no longer caring about offending them.

When he was taken into the EFCC detention building, he saw a group of people who had once guarded him in the safe house, now also in cells, under investigation for possible allowing Anjarwalla to escape and even suspected of colluding with him. Gambaryan was then placed alone in his cell.

As Gambaryan described it, the cell was like a “box” without windows, with only a cold shower with a timer switch and an untimely Posturepedic mattress. The room was covered with as many as half a dozen cockroaches of varying sizes. Despite the breathless heat in Abuja, there was neither air conditioning nor ventilation in the cells, except what Gambaryan remembers as the “loudest fan in the world” that was running day and night. “I can still hear the damn fan,” he said.

Isolated in that cell, Gambaryan said he began to feel disconnected from his body, his environment and all this hellish situation. The first night, he didn’t even think about his family. His mind was blank and he didn’t notice the cockroaches in the room.

By the next morning, Gambaryan had not eaten for more than 24 hours. Another detainee gave him some biscuits. He quickly realized that his survival depended on Ogunjobi, who would come every few days to bring him food and sometimes let him use his mobile phone, when he was briefly released from solitary confinement. Soon, Gambaryan’s former guards began to share meals sent by his family with him, but Ogunjobi came less and less frequently, sometimes even refusing to let him use his mobile phone. The young man he had taken over at the airport, who admired Gambaryan’s work, seemed completely changed. “It could almost be said that he enjoyed having control over me,” Gambaryan said.

The Nigeria he was guarding a few days ago is now Gambaryan’s only friend. He taught a young EFCC staff member to play chess, and they often played chess together during their brief free time before being put back in their cell.

A few days after being put in detention, Gambaryan’s lawyer came to see him and told him that in addition to the original tax evasion charges, he was now charged with money laundering. The new charges mean he could face up to 20 years in prison.

In his second week in detention, Gambaryan’s son turned 5 years old. On his birthday, Gambaryan was allowed to use the EFCC phone to call his family and smoke a few cigarettes, which was not allowed at other times. He spoke on the phone for 20 minutes with his wife-who he said was “devastated” by anxiety-and then chatted with the children. My son still doesn’t understand why he’s not at home. Yuki told Gambaryan that his son began crying for him when he was not expecting it, and often went to their home office and sat in his chair. Gambaryan explained to his daughter that he was still resolving legal issues with the Nigeria government. Later, he learned that two weeks after his detention, his daughter checked his name and watched the news, and she knew more than she let him know.

In addition to the occasional meetings with fellow incarcerated prisoners, Gambaryan has two books to pass the time-a Dan Brown novel given to him by EFCC staff and a “Percy Jackson” youth novel brought by lawyers. He has few other things to do to keep him busy. His thoughts cycle between angry curses, blame for himself, and emptiness.

“It’s torture,” Gambaryan said. “I knew if I stayed there, I would go crazy.”

Although Gambaryan felt extremely lonely, he was not forgotten. While he was in his cell at the EFCC, a loose group of friends and supporters had begun to respond to his calls for help in the video. However, he soon realized that if he wanted freedom, the real help would not come from the Biden administration.

Within Binance, Gambaryan’s first text message about his detention immediately triggered endless crisis response meetings, hiring lawyers and consultants, and contacting any government official who might be influential in Nigeria. Will Frentzen, a former U.S. prosecutor from the Bay Area, had handled many of Gambaryan’s major cases. After moving to work at the private firm Morrison Foerster, he took over Gambaryan’s case and became his personal defense lawyer. Gambaryan’s former colleague Patrick Hillman had handled crisis response work with former Florida Congressman Connie Mack and learned about Mack’s experience in handling hostage incidents. Mack agreed to lobby his contacts in the legislative community for Gambaryan. Gambaryan’s old FBI colleagues immediately began to pressure the FBI to promote Gambaryan’s release.

However, at the top of the U.S. government, some supporters of Gambaryan said their requests for help had been met with cautious responses. “From the first day of Gambaryan’s detention, State Department staff have worked hard to ensure his safety, health, provide legal aid, and promote his release after he was criminally charged,” a senior State Department official said in an interview with WIRED, speaking on condition of anonymity in accordance with department policy. However, according to several people involved in the matter, the Biden administration initially seemed to have an ambiguous attitude towards Gambaryan. After all, Binance has just agreed to pay a huge fine to the Justice Department, the government is not friendly to the entire cryptocurrency industry, and Binance has a poor reputation and “toxic”-as one Gambaryan supporter described it.

“They think maybe there is a case in Nigeria,” Frentzen said. “They’re not sure what Tigran was doing there. So they all chose to step back.”

Gambaryan fell into Nigeria’s predicament at an extremely dangerous geopolitical moment. The U.S. ambassador to Nigeria will retire in 2023, and the new ambassador will not officially take office until May 2024. At the same time, Niger and Chad have asked the United States to withdraw troops in both countries as the two countries are strengthening relations with Russia and Nigeria is a key U.S. military ally in the region. This makes negotiations to free Gambaryan more complex than with other countries that have wrongly detained U.S. citizens, such as Russia or Iran. “Nigeria is the only option left, and they know it,” Frentzen said. “So, the timing was really bad. Tigran is really one of the most unfortunate people in the world.”

When Gambaryan is held in the guest room, it may become clearer on the diplomatic level that he is a hostage, and former congressman Mack said he had lobbied for Gambaryan’s release. However, the criminal charges brought against him complicated the situation. “The U.S. government has followed that narrative,” Mack said.”They want to let the legal process unfold on its own.”

Frentzen and his senior colleague at Morrison Foerster and former General Counsel for the National Intelligence Agency, Robert Litt, said they began reaching out to the White House to explain to them how weak the criminal case Gambaryan faced. Of the more than 300 pages of “evidence” submitted by prosecutors in Nigeria, only two pages mentioned Gambaryan himself: one page was an email showing he worked at Binance; the other page was a scanned copy of his business card.

Despite this, in the following months, the U.S. government did not interfere in Gambaryan’s criminal prosecution. For Frentzen, this is a shocking situation: a former IRS agent who has worked for many years in the federal government and has handled many major cryptocurrency criminal cases and asset forfeiture cases in history, but in what appears to be cryptocurrency extortion, the government has only remained silent in support.

“This man helped the United States recover billions of dollars,” Frentzen recalled,”and we couldn’t get him out of Nigeria’s predicament?”

In early April, Gambaryan was taken to court for arraignment. Wearing a black T-shirt and dark green trousers, he was publicly displayed and became a symbol of the evil forces that destroyed Nigeria’s economy. As he sat in a red sofa chair listening to the accusations, local and international media flocked in, cameras sometimes just feet away from his face, he could hardly hide his anger and humiliation. “I feel like a circus animal,” he said.

During this trial, the following trial, and in subsequent court documents, prosecutors argued that if Gambaryan were released on bail, he would likely escape, citing Anjarwalla’s escape as an example. They curiously emphasized that Gambaryan was born in Armenia, although he left that country with his family when he was 9 years old. Even more ridiculous, they claimed that Gambaryan and other inmates at the EFCC Detention Facility had planned a plot to use a substitute to escape, which Gambaryan said was a ridiculous lie.

At one point, prosecutors made it clear that the detention of Gambaryan was crucial to the Nigeria government and was a lever for them to put pressure on Binance. “The first defendant, Binance, was operating in a virtual manner,” the prosecutor told the judge.”The only thing we can catch is this defendant.”

The judge refused to rule on Gambaryan’s bail and decided to keep him in custody. After two weeks in solitary confinement, he was transferred to the real prison, Kuje Prison.

Guards-including the usual Ogunjobi-took Gambaryan into a van. Ogunjobi returned the cigarettes to him, who had been smoking almost the entire hour’s drive from central Abuja, as they passed through what looked like a slum on the outskirts of the city. During the journey, Gambaryan was allowed to call Yuki and some Binance executives, some of whom had not heard from him for weeks.

On the journey to Kuje Prison, which passed through a prison known for its poor conditions and its former detention of Boko Haram suspects, Gambaryan said he felt numb,”cut off from the outside world” and completely gave up control of his destiny. “I live for an hour, a minute,” he said.

As they arrived and walked through the prison’s gates, Gambaryan saw the prison’s low buildings for the first time, with walls painted light yellow, many of which were still destroyed by an ISIS attack that allowed more than 800 prisoners to escape almost two years ago. Gambaryan’s EFCC guards took him into prison and took him to the prison governor’s office. He later learned that the prison director was closely monitoring him under instructions from National Security Adviser Ribadu.

Gambaryan was then taken to the “quarantine area,” a unit for high-risk prisoners and VIP prisoners willing to pay extra fees for special treatment. The 6-by-10-foot room has a toilet, a metal bedstead with what Gambaryan called a “simple blanket” as a mattress, and a window with metal railings. Compared with the EFCC dungeon, this room is an “upgraded version”: it has sunshine and fresh air-although contaminated by a garbage fire hundreds of meters away-and can see the trees, which fly in droves of bats every night.

Gambaryan’s first night in prison, it started to rain and a cool breeze blew in from the window. “Although the environment is very bad,” Gambaryan said,”I feel like I am in heaven.”

Soon after, Gambaryan met his neighbors. One of them is a cousin of Nigeria’s Vice President, the other is a suspect suspected of fraud and awaiting extradition from the United States, involving up to US$100 million; the third is Abba Kyari, a former deputy police chief of Nigeria, who was indicted by the United States on suspicion of accepting bribes, although Nigeria rejected the United States ‘extradition request. Gambaryan believes that Kyari’s case is more because he offended corrupt Nigeria officials.

Gambaryan said Kyari has a lot of influence in prison and that other prisoners basically work for him. Kyari’s wife would bring home-cooked meals to everyone, even the guards. Gambaryan especially likes the kind of dumplings made by Kyari’s wife from northern Nigeria, and she will make extras for him. He would share takeout with Kyari the lawyer brought from the fast food restaurant Kilimanjaro, who especially liked their Scottish eggs.

Gambaryan’s neighbors taught him the unspoken rules of prison life: how to obtain a mobile phone, how to avoid conflicts with prison staff, and how to avoid violence from other inmates. Gambaryan insists he never bribed the guards-although they sometimes demand astronomical amounts of tens of thousands of dollars-but is still protected because of his close relationship with Kyari. “He’s like my Red,” Gambaryan said, comparing Kyari to Morgan Freeman’s character in “The Shawshank Redemption.” “He is the key to my survival.”

Gambaryan’s case continued over the next few weeks, and he was regularly sent back to Abuja for hearings, at each hearing, the judge always seemed to favor prosecutors. On May 17-his 40th birthday-he attended the hearing again and his bail request was ultimately denied. That night, lawyers brought the big cake paid for by Binance and sent it to Kuje Prison, where he shared the cake with neighbors and guards.

Every night, Gambaryan is locked into his cell early, usually starting at 7 p.m., and even hours before other prisoners, while he is watched by a guard who records his every movement in a notebook, all at the orders of the National Security Adviser. He found that he could exercise by doing pull-ups on the windowsill at the entrance to the courtyard of the quarantine area. Although there were huge roaches, geckos, and even scorpions in his cell-he learned to shake the millet scorpions out of his shoes every time before putting on his shoes-he slowly adapted to prison life.

Sometimes he would wake up from a dream and dream that he was still outside, suddenly realizing that he was in this small, dirty cell, and then he would get out of bed and pace anxiously in the small space until around 6 a.m. The guard would let him out. In the end, however, Gambaryan said that his dreams also became filled with images of prison.

One afternoon in May, Gambaryan began to feel unwell while meeting with his lawyer. He returned to his cell, lay down, and vomited the rest of the night. He guessed he might have food poisoning, but the guard did a blood test and it showed he had malaria. The guard asked him to pay in cash, used the money to buy a drip of fluid, hung it on a nail on the wall of his cell, and gave him an anti-malaria injection.

Gambaryan had a court hearing the next morning. He told the guards he was too weak to walk, but they still removed the IV and forcibly put him into the car, saying it was an official order. When he arrived at the courthouse, he managed to climb the long steps, but as soon as he entered the courthouse, his vision began to blur and the room began to spin. Next, he fell to his knees. Guards helped him stand up, he slumped into a chair, and lawyers asked for a court order to take him to the hospital.

The judge issued a hospitalization order, but Gambaryan was not sent directly to a medical facility, but was sent back to Kuje Prison, where the court, his lawyers, the prison, the Office of the National Security Adviser and the U.S. State Department were discussing whether to temporarily release him because they feared he risked escape. For the next 10 days, Gambaryan lay in his cell, unable to eat or stand up. Eventually, he was taken to Nizamiye Hospital in Abuja, where he had a chest X-ray and prescribed antibiotics after a brief examination. The doctor said he was fine, but then sent him back to Kuje prison without explanation.

In fact, Gambaryan’s condition is more serious than before. His friend Chagri Poyraz, a Turkish-Canadian, eventually had to fly to Ankara to check Gambaryan’s hospital records with the Turkish government before learning that his X-rays showed he had multiple serious bacterial lung infections. A few months later, the judge in the case also asked Abraham Ehizojie, the medical director of Kuje Prison, to appear in court to explain why the hospitalization order had not been followed. Prosecutors took out Gambaryan’s medical records, saying he refused treatment and asked to be sent back to prison, but Gambaryan firmly denied this.

After returning to his cell in Kuje prison, Gambaryan had a high fever for several days, reaching 104 degrees Fahrenheit. During his brief stay in hospital, guards searched his cell and found his hidden mobile phone, so he was completely quarantined and unable to communicate with the outside world until his neighbors helped him get a new mobile phone. His body became weaker and weaker, breathing became difficult, and his body temperature never subsided. Gambaryan gradually felt that he might not survive. At one point, he called Will Frentzen and told him he might be in critical condition. However, officials at Kuje prison still refused to send him back to the hospital.

Despite this, Gambaryan did not die. But he lay in bed for nearly a month before he was finally able to stand up and eat again. He lost nearly 30 pounds since he was imprisoned.

One day, as he was recovering in his cell, the guard told him that guests were visiting him. Although he still felt weak, he walked slowly to his office in front of the prison. After entering the door, he saw two members of the U.S. Congression-French Hill and Chrissy Houlahan, from two parties. Gambaryan could hardly believe they were real-they were the first Americans he had met in months, except for low-level State Department officials who occasionally visited him.

For the next 25 minutes, they listened to Gambaryan describe the harsh conditions in the prison and his life-and-death experience with malaria and later pneumonia. Hill recalled Gambaryan’s voice was so soft that the two lawmakers had to lean forward to hear what he was saying, especially under the noise of fans.

Sometimes Gambaryan’s eyes filled with tears, because the pain of loneliness and the fear of dying finally made him unable to help himself. “He looked like someone who was sick, weak, emotionally broken and really needed a hug.” Hill said. Two lawmakers each gave him a hug and said they would work hard for his release.

He was then taken back to his cell.

The next day, June 20, Hill and Khorahan recorded a video on the tarmac at Abuja Airport. “We have asked our embassy to promote Tigran’s humanitarian release, considering the harsh conditions in the prison, his innocence and his health,” Hill said into the camera. “We hope he can go home and let Binance and the Nigeria take care of the rest themselves.”

Connie Mack’s conversations with his old friends had an effect: During a subcommittee hearing on U.S. citizens detained by foreign governments, Gambaryan’s Georgia Congressman Rich McCormick argued that Gambaryan’s case should be treated as a hostage case held by a foreign government. He cited the Levinson Act, which required the U.S. government to assist wrongfully detained citizens. “Is U.S. diplomatic intervention necessary to ensure the release of detainees? Absolutely yes, absolutely yes.” McCormick said at the hearing. “This person deserves better treatment.”

At the same time, 16 Republican lawmakers signed a letter asking the White House to treat Gambaryan’s case as a hostage case. A few weeks later, McCormick proposed the request as a parliamentary resolution. More than a hundred former federal agents and prosecutors have also signed another letter asking the State Department to intensify its efforts to help resolve the issue.

According to multiple sources, FBI Director Christopher Wray raised Gambaryan’s case during a meeting with President Tinubu during a visit to Nigeria in June. Since then, Nigeria’s tax authority FIRS dropped the tax evasion charge against Gambaryan. However, more serious money laundering charges filed by the EFCC remain and still threaten his decades-long imprisonment.

Gambaryan’s supporters have been hoping for months that Nigeria can finally reach a deal with Binance to end his prosecution. However, Binance representatives said that by then, they seemed unable to offer terms that would interest Nigeria, and Nigeria no longer even hinted that it would accept any payment. Whenever they feel they are close to reaching an agreement, requirements change, officials disappear, and the agreement breaks down. “It’s like the story of Lucy and football,” said Deborah Curtis, a lawyer at Arnold & Porter and former CIA deputy general counsel, who was providing legal services to Binance.

As the summer wore on, Gambaryan supporters began to believe that negotiations between Nigeria and Binance had reached a dead end and that the criminal case had progressed far enough that Binance alone could not set Gambaryan free. “It’s starting to become clear,” Frentzen said.”This matter can only be resolved through the U.S. government-otherwise there is no hope.”

At the same time, Gambaryan’s health deteriorated again. Lying on the metal bedstead for a long time aggravated the old back injury he suffered during IRS-CI training more than a decade ago. He was later diagnosed with disc herniation-the outer layer of soft tissue between the vertebrae ruptured, causing the inner cushion to protrude, compressing nerves and causing severe persistent pain.

By August, Gambaryan told me via text message that he was “almost paralyzed.” He had been out of bed for weeks and was still taking blood thinners to prevent blood clots in his legs due to lack of exercise. He wrote that every night he was unable to fall asleep because of the pain, and usually didn’t feel sleepy until 5 or 6 a.m. or even couldn’t read. Occasionally, he would call his family, chat with his daughter, and listen to her play a Japanese role-playing game called “Omori,” a computer he had installed for her until she slept in Atlanta. Then, a few hours later, he would fall asleep.

Despite visits from members of Congress and growing calls for his release, Gambaryan appears to be in almost despair and is at his lowest point in prison.

“I tried to pretend to be strong in front of Yuki and the children, but the situation was really bad,” he wrote to me. “I’m really in a dark place now.”

A few days later, a video appeared on X platform showing Gambaryan limping into the courtroom with a crutch, dragging one foot. In the video, he asks for help from a guard in the corridor, but the guard even refuses his request. Gambaryan later told me that court staff were instructed not to allow any help or use a wheelchair, fearing that it would arouse public sympathy.

“This is fucking bad! Why can’t I use a wheelchair?” Gambaryan shouted angrily in the video. “I am an innocent person!”

“I am a fucking human being!” Gambaryan continued, his voice almost choked up. He took a few steps with difficulty with his crutch, shook his head in disbelief, and then leaned against the wall to rest. “I can’t do it.”

If the order at the time was to prevent Gambaryan from arousing sympathy when he entered the courtroom, it would have been completely counterproductive. The video quickly spread online and was viewed millions of times.

By the fall of 2024, the U.S. government finally seemed to have reached a consensus that it was time for Gambaryan to go home. In September, the House Foreign Affairs Committee passed a bipartisan resolution approving McCormick’s bill to prioritize Gambaryan’s case. “I urge the State Department, I urge President Biden: put more pressure on the government of Nigeria,” Congressman Hill said at the hearing. “It must be realized that an American citizen is kidnapped and imprisoned by a friendly country and has nothing to do with him.”

Some supporters of Gambaryan revealed that they had heard that the new ambassador to Nigeria had also frequently raised Gambaryan’s situation to Nigeria officials and even President Tinubu, so that at least one minister blocked the ambassador on WhatsApp.

During the United Nations General Assembly in late September, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations raised Gambaryan’s case during a meeting with Nigeria’s foreign minister and emphasized the need for his immediate release, the minutes of the meeting read. Binance, meanwhile, hired a truck with digital billboards to drive around the United Nations and midtown Manhattan to show Gambaryan’s face and called on Nigeria to stop his illegal imprisonment.

At the same time, White House National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan spoke on the phone with Nigeria National Security Adviser Nuhu Ribadu, basically demanding Gambaryan’s release, multiple sources involved in promoting Gambaryan’s release said. One of the most influential news was that several supporters said that U.S. officials had made it clear that Gambaryan’s case would become an obstacle to talks between President Biden and Nigeria President Tinubu at the United Nations General Assembly or elsewhere, which deeply troubled Nigeria.

Despite all this pressure, the decision to release Gambaryan remains in the hands of the Nigeria government. “For a while, Nigeria realized that this was a very bad decision,” said a Gambaryan supporter who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitive nature of the negotiations. “After that, the question becomes whether they give in, whether they persist because of self-esteem, or because they have no way to go back.”

One day in October, during the long drive from Kuje to the Abuja court-by then Gambaryan had lost count of how many court trials he had gone through-the driver received a phone call. He talked for a while, then turned the car and returned to prison with Gambaryan. After arriving at the prison, he was taken to the front desk and told that he could not go to the court because he was unwell. That was a statement, not an inquiry.

After returning to his cell, Gambaryan called Will Frentzen, who told him that might mean they were finally ready to send him home. After many dashed hopes over the past eight months, Gambaryan did not easily believe the news.

A few days later, the court held a hearing, but Gambaryan did not attend. Prosecutors told the judge that they had decided to drop all charges against Gambaryan because of his health. Kuje prison officials spent the whole day processing documents, then took him out of his cell, brought him the suitcase he had brought on his trip to Abuja, and took him to the Abuja Continental Hotel. Binance reserved a room for him, arranged for private security guards, and invited a doctor to examine him to make sure he was healthy enough to fly. For Gambaryan, it all came so suddenly, and after so many months of hopeless waiting, it was almost unbelievable.

The next day, on the runway at Abuja Airport, Nigeria officials returned his passport to him-although they first argued over the US$2000 fine he was fined for expired visa. State Department staff helped him get up from his wheelchair and board a private jet equipped with medical equipment. What Gambaryan didn’t know was that Binance staff had been preparing for the flight for weeks-Nigeria officials had told them Gambaryan would be released but regretted-and they had even arranged a flight for him over Niger, which Niger officials signed the consent less than an hour before takeoff.

On the plane, Gambaryan took a few bites of salad, fell asleep on the sofa, and woke up in Rome.

Binance arranged for a driver and private security guard to pick him up at the Italian airport and take him to an airport hotel for the night before flying back to Atlanta the next day. At the hotel, he called Yuki and then Ogunjobi-his former friend in Nigeria and the person who advised him to return to Abuja months ago.

Gambaryan said he wanted to hear how Ogunjobi explained himself. When he called, Ogunjobi began to cry on the phone, apologized repeatedly, and thanked God that Gambaryan was finally released.

Gambaryan couldn’t bear all this. He listened quietly but did not accept the other party’s apology. Just as Ogunjobi was pouring out, he noticed a phone call from an American friend, a Secret Service agent he had worked with. Gambaryan didn’t know it at the time that the agent was in Rome for a meeting with his former boss, Jarod Koopman, head of the IRS-CI Cybercrime Unit, who were planning to bring him beer and pizza.

Gambaryan told Ogunjobi he had to hang up and ended the call.

On a cold, windy day in December, former federal agents, prosecutors, State Department officials and congressional aides gathered in a luxurious room in the Rayburn House office building to talk. One by one, members of Congress came in and shook hands with Tigran Gambaryan, who was wearing a dark blue suit and tie, with a neatly trimmed beard and shaved hair. Although he limped slightly from emergency spinal surgery in Georgia a month ago, his pace remained firm.

Gambaryan took photos with every lawmaker, aide, and State Department official and talked to them, thanking them for their efforts to bring him home. When French MP Hill said he was happy to see him again, Gambaryan joked that he hoped he smelled better this time than when he was in Couje.

The reception was just one of a series of VIP receptions Gambaryan received after returning to his country. At the Georgia airport, Senator McCormick came to greet him and presented him with an American flag that had been flying over the Capitol all day long. The White House also issued a statement saying that President Biden had called President of Nigeria to thank President Tinubu for facilitating Gambaryan’s release on humanitarian grounds.

I later learned that the statement of thanks was part of an agreement between the U.S. government and Nigeria, which also included assisting Nigeria’s investigation of Binance, which is still ongoing. Nigeria continues to prosecute Binance and Anjarwalla in absentia. A Binance spokesman said in a statement that the company was “relieved and grateful” that Gambaryan had returned home smoothly and thanked all those who worked hard for his release. “We urgently hope to put this incident in the past and continue to work for a better future for the blockchain industry in Nigeria and the world,” the statement read. “We will continue to defend ourselves against baseless accusations.” Nigeria government officials did not respond to WIRED’s multiple interview requests about the Gambaryan case.

After the reception, Gambaryan and I took a taxi and left together. I asked him what he planned to do next. He said if the new administration is willing to accept him, he may return to government work-also depending on whether Yuki is willing to accept moving back to Washington again. Cryptocurrency news website Coindesk reported last month that he had been recommended by some crypto industry people with ties to President Trump for a senior position in the SEC’s head of cryptoassets or in the FBI’s cyber division. Before considering this, he said vaguely: “I may need some time to clear my thoughts.”

I asked him how his experience in Nigeria had changed him. He replied in a strangely relaxed tone: “I guess it does make me angrier?” He seemed to be thinking about this for the first time. “It makes me want to get back at the people who did this to me.”

For Gambaryan, revenge may be more than just a fantasy. He is filing a human rights case against the Nigeria government in a case that began when he was detained and he hopes to investigate Nigeria officials who he believes have held him hostage for more than half a year. He said he sometimes even sent messages to officials he believed were responsible, telling them: “You will see me again.” He said what they had done “shamed the badge” and that he could forgive what they had done to him, but not what they had done to their families.

“Am I stupid to do this? Maybe,”he told me in the taxi. “I was in severe back pain and I was lying on the floor. It was so boring.”

As we got out of the car and went to his hotel in Arlington, Gambaryan lit a cigarette and I told him that although he himself said he was angrier than before he was imprisoned, it seemed to me that he was calmer and happier than in previous years-I remember reporting on his continuous crackdown on corrupt federal agents, cryptocurrency launderers and child abusers, he always gave me the impression of being angry, motivated, and unremittingly pursuing the targets of investigations.

Gambaryan responded that if he seemed more relaxed now, it was only because he was finally home-he was grateful to see family and friends, to be able to walk again, to be free from conflicts between forces greater than himself, conflicts that had nothing to do with him. To get out of prison alive and not die there.

As for the drive of anger in the past, Gambaryan disagreed.

“I’m not sure it was anger.” He said,”That’s justice. What I want is justice, and I still do.”

original link