Young people sing like the wind, and middle-aged people cycle like a bell.

Your song cutting speed is exposing your age

author| Gan Lei, the first voice of music

When headphones transform into the spiritual barrier of contemporary people, do you prefer a fixed song list to loop over and over again, or do you leave the choice to the algorithm? When the song you play is not your favorite, do you quickly cut the song or choose to continue listening?

As everyone knows, every time you cut a song is a miniature negative vote. This seemingly casual fingertip movement is quietly becoming an age detector in the digital age.

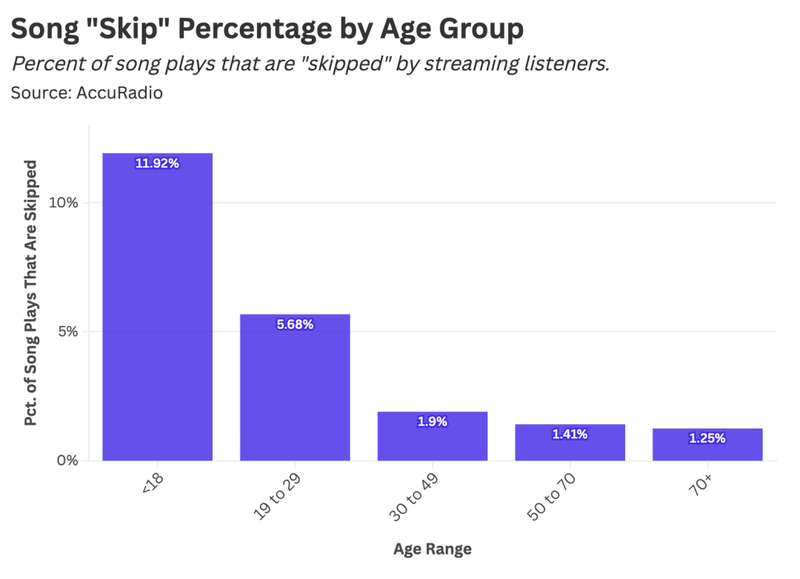

A recent study by the Stat Significant platform on users of Internet radio station AccuRadio revealed the generation gap in listening habits of people of different ages. Users born in the 2000s have to cut songs once every 10 songs on average, practicing the survival rules of music king; while the 70s and 80s generations, which have gone through the years of tapes and records, have long become accustomed to having single cycles 1000 times, just like meditation in the digital age. ritual.

This migration from a music sea king to a nostalgic nail house quietly burned everyone’s age coordinates into the genes of the playlist.

Young people sing like the wind, and middle-aged people cycle like a bell

When you tap the recommendation button on the music APP, a music blind box journey full of surprises quietly begins.

As the unknown melody hits your eardrums, you just tap the screen to decide to skip or play, giving a yes or no response. Behind this simple operation, the streaming media platform has been tracking every song cut action you make in real time, recording the nodes where the track is interrupted, analyzing the types of songs you have listened to completely, and at the same time combining information such as your age to continue to outline exclusive user portraits.

Data from Stat Significant shows that on the AccuRadio platform, the frequency of song cuts among users under the age of 18 is as high as 11.92%, while the frequency of song cuts among those over the age of 30 is less than 2%. Such sharp differences in data may be misleading at first glance. On the surface, young people frequently cut songs to music seems to mean that they are not aesthetically tolerant and always reject novel songs that are not suitable for their tastes. In contrast, older listeners seem to be more willing to accept songs recommended by the APP.

However, when we explore the differences in the scope of music exploration among users of different ages, we can clarify the facts behind them.

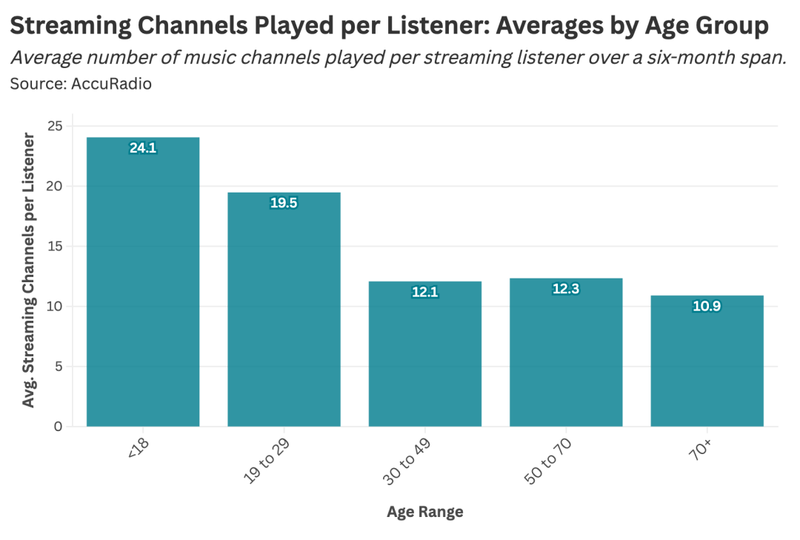

Statistics show that young users under the age of 18 frequently listen to an average of 24.1 music channels on the AccuRadio platform, which is nearly twice that of users over the age of 30. Many middle-aged and elderly users rarely rely on platform algorithm recommendations, but are accustomed to listening to a few song lists repeatedly, or even cycling a certain song with a single. Daniel Parris, a senior data analyst, shared that when he was writing Python code at work, he often repeated My Chemical Romance’s “Welcome to the Black Parade” or Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark”, which has been played no less than thousands of times.

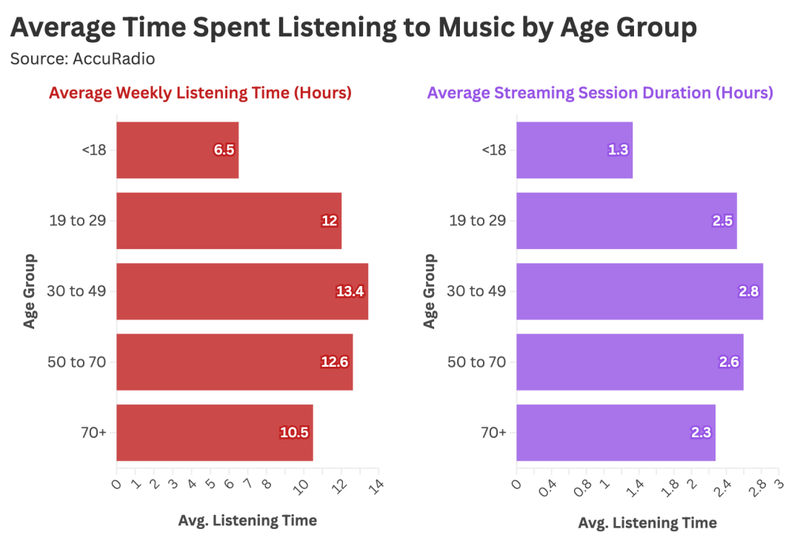

Another set of data from Stat Significant reveals differences in listening time among AccuRadio users of different ages. 30-49 The average user of the year old has the longest listening time per day, reaching 2.8 hours, and the cumulative usage time per week reaches 13.4 hours. However, most of the time, they only cycle through a limited song list and a few favorite songs.

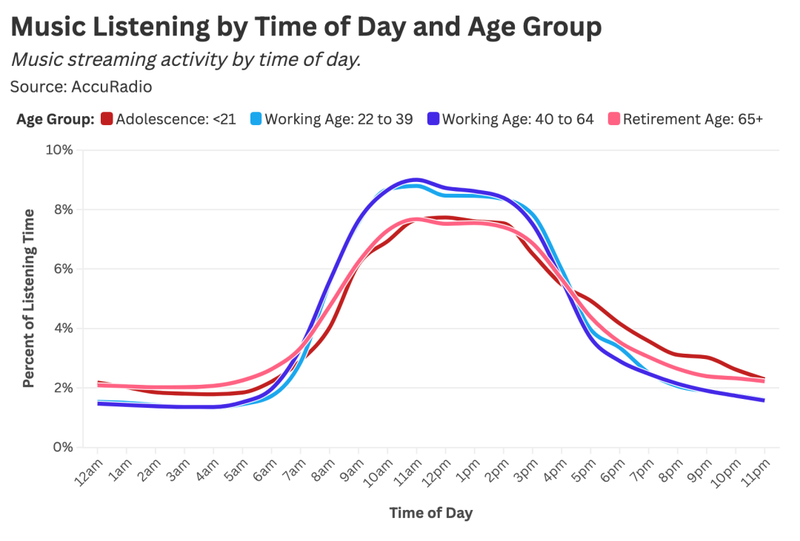

In terms of usage periods, users ‘peak music playback periods are concentrated from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., especially those aged 22-39 and 40-64, have a higher playback rate than other age groups. It can be seen that office workers like to use music to isolate external interference and relieve stress when commuting and working, and are more inclined to choose familiar songs, thus constituting their unique music consumption scene.

Daniel Parris joked that he would occasionally have the idea to try new playlists and channels. At first, he would feel brave, but this enthusiasm was often difficult to last. Usually within ten minutes, he would return to his familiar song list and return to the musical comfort zone he originally created.

After all, in the face of the pressures and uncertainties of life, familiar songs can be like an old friend, giving people the sense of security they crave deep down.

From music king to affectionate single-mindedness, is it growth or compromise?

Why are we less willing to cut songs as we grow up?

Young users cut songs at high frequencies, which is actually a natural path for digital aborigines to explore music aesthetics. When they are immersed in the music sea of 100,000 new tracks per day, the digital trajectory formed by swiping their fingertips is like a large-scale auditory pioneer journey. In the maze of algorithms, young people quickly shuttle through electronics, City Pop, Indie rock and other diverse genres, maintain their enthusiasm for exploration, and find their favorite tunes through frequent screening.

In mirror contrast to this is the auditory anchoring effect exhibited by mature groups. Users over the age of 30 often lock in a small number of playlists and repeatedly listen to familiar melodies wrapped by time in commuting, work, housework and other scenes to gain emotional comfort. This selective repetition mechanism is actually an emotional energy-saving strategy in the streaming media era. When cognitive bandwidth is occupied by survival pressure, familiar music is often the spiritual catalyst with the lowest energy consumption.

Obviously, with the increase of age, individuals ‘musical functional needs gradually shift from exploration and discovery to emotional maintenance, and the adolescent effect of music aesthetics confirms this point.

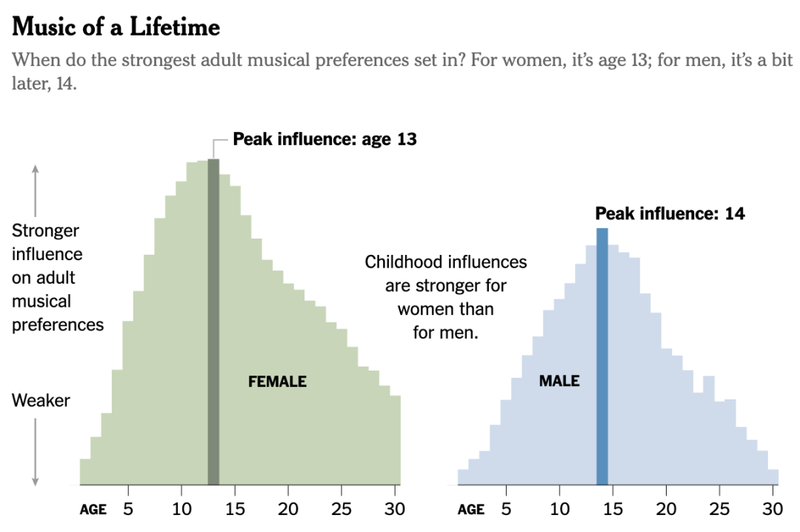

A 2018 New York Times statistics on Spotify users showed that the most played songs people usually originated from puberty. Regardless of men and women, the songs they are exposed to when they are on average 13-14 years old can often lay the foundation for future musical taste. After entering adulthood and even middle age, people’s music choices only strengthen or weaken existing preferences formed during adolescence, and these preferences are difficult to truly shake.

In fact, as early as the 1980s, the open-eardness theory proposed by British educational psychologist David Hargreaves revealed that minors are usually more actively exploring different musical styles, and this desire for exploration is a positive construction of cultural identity. It is precisely because the youth is in the sensitive stage of open hearing that the music you are exposed to at this time often accumulates as an important anchor point of intergenerational cultural identity. A survey by streaming media platform Deezer further shows that people’s musical tastes are basically solidified by the age of 31.

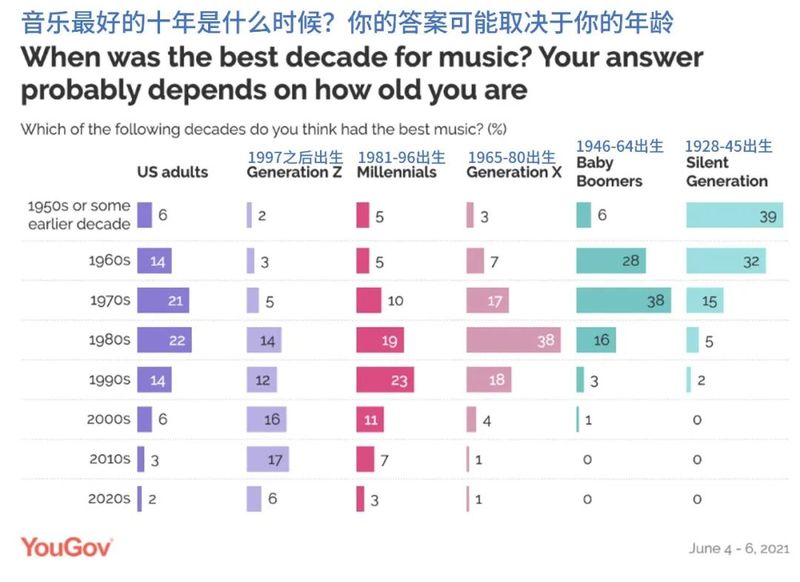

YouGov’s research data provides vivid evidence for this. When asked about their musical aesthetic preferences, the older the interviewees, the more inclined they are to think that the music of my era was better. This cognitive difference deeply rooted between generations is like annual rings, clearly dividing the auditory boundaries of different generations.

In addition, the frequency of song cutting and the decline in the desire to explore music are also deeply related to the changes in social needs at different stages of life.

Veteran music journalist Henry Chandonnet once pointed out: For Generation Z, music itself can become their social media. rdquo; During his youth, frequent musical exploration of songs is undoubtedly an important ritual for accumulating social capital. Whether it’s hit singles in Short Video or list topics on music apps, teenagers seek identity by constantly updating their music conversation content.

The product logic of the streaming media platform confirms this trend. Natasa Soltic, product director at Spotify, mentioned that the content shared by young users has expanded from playlists to unpopular song ratings, listening statistics and even interesting lists, and these have become a highlight of personality. Digital tattoos.

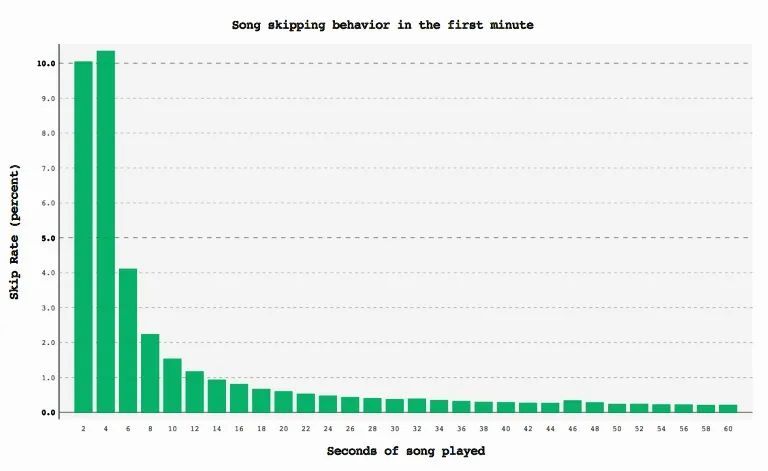

Under the constraints of the attention economy, this kind of social music consumption comes with a screening mechanism: users are exposed to hundreds of songs every day, but 90% of auditions are skipped within the first 30 seconds. The seemingly inefficient exploration process achieves the core step of social interaction through music sharing to complete information exchange, while judging the likes and dislikes of the music itself takes a second place.

As people grow older, people’s social circles gradually stabilize, the social attributes of music change from capital accumulation to spiritual resonance, and the cycle of old songs gradually replaces fresh exploration, and people with common music interests are more likely to gather to form Social networks.

It is undeniable that middle-aged and elderly people repeatedly cycle classic songs due to their feelings and activate platform algorithms, which has become an important force in promoting the popularity of old songs. For example, some time ago, Daolang returned to public view after a long period of silence. The reason why cross-generational communication can be quickly achieved is that the long-term circulation of middle-aged and elderly groups cannot be ignored.

When you are young, music is a ticket for adventure, and singing is a map to explore the unknown; when you are older, music is a haven from the wind, and familiar songs are like shortcuts that go straight to your heart.

Is the music platform stuck in the generation gap?

While many streaming media platforms are trying to bridge the intergenerational gap with unified algorithms, data has opened a profound cognitive gap. The intergenerational differences in music consumption are essentially two different dimensions of perception of time and space. Young users measure the value of music in seconds, while middle-aged and elderly users accumulate emotional concentration in years.

According to research by data analyst Paul Lamere, taking Spotify as an example, if a user chooses to skip a song, the probability of cutting the song in the first 5 seconds is 24.14%, 28.97% in the first 10 seconds, and 35.05% in the first 30 seconds. It can be more intuitively seen from the chart that for songs they dislike, there is a high probability that users will cut the song within the first 5 seconds.

This five-second trial phenomenon reflects the music consumption characteristics of contemporary young people: they are like experienced mineral prospectors, who instantly judge whether it is worth paying attention based on the prelude guitar chords or drum beats. Today’s popular song production is also catering to this lightning screening mechanism, adapting young people’s nerve reflexes by strengthening prelude memory points and shortening the emotional preparation time, and completing the auditory assault in a short time through iconic electronic sound effects.

In contrast, pushing songs to middle-aged and elderly users is more like a protracted battle, often requiring hundreds of infiltrations. For them, music consumption is more like the tasting process of old Pu ‘er. In addition, when middle-aged and elderly users hear songs they don’t like in scenes such as work, housework, and sleeping assistance, they sometimes tend to turn down the volume rather than directly cut the song. This gentle refusal reflects their tolerance for streaming media.

As Daniel Parris summarizes, as people age, music was first a means of exploring cultural identity, later a spiritual barrier in commuting and work, and eventually returned to its purest emotional entertainment purposes.

When the post-00s use the speed of song cutting to measure the freshness of the world, and the post-70s use the number of cycles to seal the temperature of memories, streaming media platforms have become a battlefield for intergenerational cognitive confrontation. The real way to break the situation is not to use algorithms to smooth out differences, but to allow music narratives of different generations to find their own chords under the digital dome.

After all, those skipped preludes and repeated chorus together constitute the most authentic annual ring mark in the human emotional spectrum.

It is not allowed to reproduce at will without authorization, and the Blue Whale reserves the right to pursue corresponding responsibilities.

![Cailian Auto Morning Post [February 22]](https://gushiio.com/wp-content/themes/boke2/thumb.php?src=https://gushiio.com/wp-content/themes/boke2/assets/img/default.png&w=243&h=156)