Holding cash in hand is not the optimal solution, and I prefer to own a good company.

After Buffett’s 60 years at the helm, Berkshire’s market value has increased 55,000 times, making it the largest paying company in the United States

Photo source: Visual China

Blue Whale News, February 23 (Reporter Ao Yulian)Selling Apple first, then Bank of America and Citigroup, Long Only Buffett will start to go retrograde in 2024: selling U.S. stocks and hoarding cash. External analysis: Release the signal that U.S. stocks are overvalued?

On the evening of February 22, Beijing time, Berkshire Hathaway announced its 2024 financial report and Buffett’s annual letter to shareholders. Buffett responded in the letter: Holding cash in hand is not the optimal solution, and he prefers to own a good company.

Blue Whale News compiled the key data points and wonderful opinions of the financial report and shareholder letters:

1. Berkshire’s performance exceeded expectations: In 2024, the company’s net profit was US$88.995 billion, down from US$96.223 billion in 2023, but far exceeded market expectations of US$60.706 billion.

2. The market value is now surprisingly compound interest: From 1965 to 2024, Berkshire’s market value per share compound annual growth rate was 19.9%; from 1964 to 2024, the market value growth rate was as high as 5502284%, or 55,000 times, exceeding the 390-fold growth rate of the S & P 500 index.

3. Selling U.S. stocks, the concentration of positions in the top five declined: At the end of the year, American Express, Apple, Bank of America, Chevron and Coca-Cola accounted for 71% of the total fair value of equity investments, which was slightly scattered from the previous 79%. In the fourth quarter, Apple sold Citibank (its shareholding decreased by 73.5% month-on-month) and Bank of America (reduced its holdings of 117 million shares), and Apple’s position fell to 300 million shares from 905 million shares at the beginning of the year.

4. Floating profits from investment by Japan’s top five trading companies: The value of their shareholding in Japanese companies such as Itochu Corporation and Mitsubishi Corporation increased to US$23.5 billion, which exceeded 70% of the cost price of US$13.8 billion.

5. Cash reserves hit a record high: At the end of the year, Berkshire’s cash and short-term government bonds and other liquid assets reached US$334.2 billion, a record high.

Wonderful views on shareholder letter:

1. Berkshire can also make mistakes, and personnel decisions cause more pain than miscalculation of financial decisions. Munger said mistakes don’t disappear into thin air, and the best way is to solve them immediately and not procrastinate.

2. Berkshire selects successors regardless of academic qualifications. A large part of its business talent is innate, and nature trumps education. After Greg Abel took over as CEO, he would also write an annual shareholder letter. He understood that shareholders could not be deceived. If you talk nonsense, you will eventually deceive yourself.

3. Sixty years ago, Buffett took over Berkshire, which was on the verge of bankruptcy. Sixty years later, Berkshire has become a major taxpayer in the United States: in 2024, it will pay US$26.8 billion to the U.S. Treasury (not including state taxes), accounting for 5% of all corporate taxes in the United States.

4. Berkshire Hathaway shareholders have only received cash dividends once. I can’t even remember why I did this now. It’s a nightmare. For 60 years, shareholders have supported the company to reinvest profits rather than dividends. Through reinvestment, we participated in the miracle of compound interest brought about by the development of the United States.

5. We will always invest most of our money in stocks, mainly U.S. stocks (whether controlling or holding), rather than preferring to hold cash. Because if fiscal policy gets out of control, the value of paper money may evaporate.

6. Unlike the fate of mankind aging with age, Berkshire today is much younger than it was in 1965. We have accumulated money and people, and Berkshire’s business has penetrated every corner of the United States.

7. Berkshire shareholders will pay more taxes to Uncle Sam, please use this money to help people who have made no mistakes in life but are at a disadvantage. They deserve better treatment.

8. Holding and shareholding have their own advantages and disadvantages. Shareholding cannot make major decisions and corrections, such as changing company management, and a good company like Apple cannot buy most of the equity; the exit cost of the shareholding test is high and it cannot flexibly enter and exit the market.

9. In the future, they may increase their holdings in Japan’s top five trading companies, and their shareholding will last for decades. At first, Buffett was attracted by the low stock price. Later, he found that the five major trading companies were excellent in capital allocation, management capabilities, and attitude towards investors. They also appropriately increased dividends, reasonably bought back shares, and executive compensation was far less aggressive than that of their American counterparts.

10. The 2025 shareholders ‘meeting will be held in Omaha on May 3. Buffett, Greg and Ajit will answer everyone’s questions together. This year, the film screening will be cancelled, and the commemorative edition of the book “60 Years of Berkshire Hathaway” will be launched at the event, which includes Munger’s little-known photos, quotes and stories.

The following is the full text of Buffett’s letter to shareholders in 2024. It was translated by AI and Blue Whale News made adjustments in the Chinese context.

The letter to shareholders is part of Berkshire’s annual report, and we are obligated to report company matters to shareholders on a regular basis. Not only should we provide financial data, but we should also share some of our investment philosophy and way of thinking. We will treat shareholders seriously as we expect to be treated.

Every year, we review the performance of companies in which Berkshire holds shares. When discussing specific subsidiaries, we try to follow the advice given by Tom Murphy 60 years ago: praise should be specific and criticism should be general. rdquo;

1. Berkshire makes mistakes

We also make mistakes, whether it’s choosing investment targets or making personnel decisions.

There are times when I make mistakes when evaluating the future economic prospects of companies Berkshire acquires, and every time it is a capital allocation mistake. This situation appears not only in the judgment of listed stocks, but also in the wholly-owned acquisition of the company.

Sometimes, I make mistakes in judging the ability and loyalty of Berkshire employees. The pain caused by misjudgment of loyalty sometimes exceeds the financial loss, and the pain is close to that of a failed marriage.

When it comes to personnel decisions, we don’t expect to find the right person every time, we just expect to make fewer mistakes. The biggest mistake is not correcting mistakes, as Charlie Munger said, procrastinating. Munger told me that problems don’t disappear into thin air, but require action.

Between 2019 and 2023, I used the term error or mistake 16 times in my letters to shareholders. During the same period, most large companies rarely publicly admitted their mistakes, but Amazon made some extremely candid reflections in its 2021 shareholder letter. In other cases, organizations usually have optimistic words and beautiful promotional pictures.

I have served on a number of large public companies where mistakes or mistakes are a prohibited term at board meetings or analyst conference calls. This culture of taboos, which implies perfection in management, always makes me uneasy (of course, in some cases, it may be wise to limit discussion due to legal factors, given that we live in a highly litigious society).

2. The unique Pitliger

Let me pause for a moment and tell you the story of Peter Ligel. Most Berkshire shareholders may not know him, but he did contribute billions of dollars to Berkshire’s wealth growth. In November 2024, Pitt passed away at the age of 80, still working.

On June 21, 2005, I first heard about Pitt’s founding Forest River, an India-based RV manufacturer. That day, I received a letter from a middleman detailing the company and saying that Pitt wanted to sell 100% of Forest River to Berkshire and made a direct offer. I liked this straightforward approach.

Later, I checked with some RV dealers. I was satisfied with the company and met with Pete in Omaha seven days later (June 28). He came with his wife and daughter, and he assured me that he wanted to continue running the company, but wanted to ensure the financial security of his family first.

During the meeting, Peter also mentioned that he then rented some properties to Forest River. In just a few minutes, we negotiated the price of this asset. I said I didn’t need Berkshire to conduct a valuation, but accepted his valuation directly. Then I asked Pete how much he needed for salary, and no matter how much he said, I would accept it. (I must add that I do not recommend this practice for general purposes.)

Pete paused, and his wife, daughter and I leaned forward. Then he surprised us: Well, I read Berkshire’s proxy, and I don’t want to make more than my boss, so give me $100,000 a year. But for the part that I earn more this year than last year, I hope to get 10% as an annual bonus. rdquo;

I replied: Okay, Pete, but if Forest River makes any major acquisitions, we will make appropriate adjustments to the additional capital used as a result.” rdquo; At the time, I did not define it appropriately or significantly, but these vague terms never caused problems.

The four of us then went to the Happy Valley Club in Omaha for dinner. Over the next 19 years, Pitt performed so impressive that no competitor could match him. Not every company has a clear and understandable business model, and not every boss is like Pete.

When dealing with people and acquiring companies, I inevitably make mistakes, and I also have psychological expectations to make mistakes. But in this process, we also encountered many surprises, whether it was the potential of the company or the ability and loyalty of the manager.

Our experience is that the right decision can have an amazing impact in the long term. For example, GEICO as a business decision, Ajit Jain as a management decision, and my good fortune in finding Charlie Munger as a unique partner, personal consultant and committed friend.

Mistakes are like passing clouds that will eventually dissipate, but the light of winners will never fade.

3. Greg Abel is about to take over from Buffett

At the age of 94, Greg Abel will soon succeed me as CEO and will write the annual letter. Gregg agrees with Berkshire’s philosophy that the report is owed annually to shareholders by Berkshire’s CEO.

He also understands that if you start deceiving your shareholders, you will soon believe your own nonsense and eventually deceive yourself.

One thing to be clear is that when selecting a CEO, I never look at the candidate’s graduate school.

There are many outstanding managers who graduated from prestigious schools, but there are also many people like Pete whose schools are not well-known and some even have not completed their studies at all. Bill Gates, for example, believes that getting started in an explosive industry that will change the world is far more important than staying in school and other diplomas. (Read his new book, Source Code.)

Not long ago, I met Jessica Thunkel over the phone, whose step-grandfather Ben Rosanna had run a business for Munger and me many years ago. Ben was a retail genius, and I remember his education was limited. In order to write this shareholder report, I specifically confirmed with Jay’s granddaughter, and her reply was that she had not even finished sixth grade.” rdquo;

I have the privilege of receiving education at three excellent universities and I firmly believe in lifelong learning. However, I have observed that a large part of business talent is innate, and nature trumps nurture. Pete of Forest River is a natural talent.

4. Performance in 2024

In 2024, Berkshire exceeded my expectations, even though 53% of our 189 operating companies reported declining profits. As Treasury yields have increased, we have significantly increased our holdings of these highly liquid short-term securities, and investment income has increased significantly and predictably.

The profits of our insurance business have also increased significantly, with GEICO (the fourth largest auto insurance company in the United States) performing particularly well. Over the course of five years, Todd Comes, Berkshire’s investment manager, introduced major reforms to GEICO, improved efficiency and updated underwriting practices.

GEICO is a long-held pearl that requires major renovations, and Todd spared no effort to complete the work. Although this work has not yet been completed, the improvements in 2024 are impressive.

Overall, in 2024, the pricing of property and accident insurance will increase, and losses caused by convective storms will increase significantly. There have been no catastrophic events in 2024, but climate change may have arrived, and one day a staggering insured loss will occur, and there is no guarantee that it will only occur once a year.

Property and casualty insurance is very important to Berkshire.

Total profit from railway and utility operations, two major businesses other than Berkshire Insurance, also increased. There is still a lot of room for development in these two businesses. At the end of 2024, our shareholding in utility operations increased from approximately 92% to 100%, spending approximately US$3.9 billion, of which US$2.9 billion was paid in cash and the rest in Berkshire’s B shares.

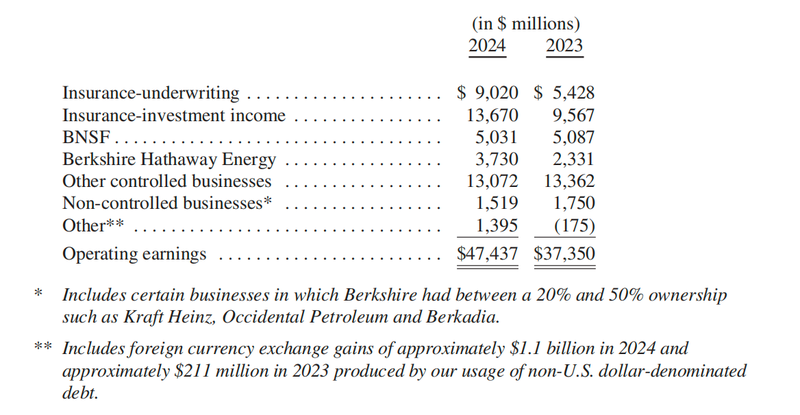

In 2024, we achieved operating profit of US$47.4 billion. Compared with the profits shown in accordance with General Accounting Standards (GAAP) requirements on page K-68 of the annual report, operating profits can more accurately reflect the operating conditions. The metrics we use exclude capital gains or capital losses on the stocks and bonds we hold. In the long run, we believe there is a high probability that gains will win, otherwise why would we buy these securities?

Although annual numbers fluctuate violently and are difficult to predict, in many cases our thinking latitude spans decades. These long-term investments will make cash registers ring like church bells.

Here is the profit breakdown we saw in 2023-2024. All calculations are made after depreciation, amortization and income tax. EBITDA is a commonly used indicator on Wall Street, but it has some flaws and is not applicable to us.

5. Surprise! We broke the American record

We took over Berkshire 60 years ago, and Charlie quickly discovered my mistake: although the price seemed cheap, it was a large northern textile company and the industry was in decline.

The U.S. Treasury Department has actually sounded the alarm. In 1965, the company did not pay a penny of income tax, and this situation has lasted for ten years. This was a dangerous signal. Textile was a pillar of American industry at that time, suggesting that Berkshire was gradually declining.

But time flies, and 60 years later, the Treasury Department certainly did not expect that this company, still called Berkshire Hathaway, the U.S. government collects more corporate income tax from it than any other company, even a U.S. technology giant with a market value of one trillion yuan.

In 2024, Berkshire paid four taxes to the IRS, totaling $26.8 billion, which accounts for approximately 5% of the total tax paid by all U.S. companies. (In addition, we pay considerable income taxes to foreign governments and 44 U.S. states.)

Here’s a key factor: From 1965 to 2024, Berkshire shareholders received only one cash dividend. The only cash dividend was on January 3, 1967, with a total dividend of US$10.18, equivalent to 10 cents per Class A stock. (I can’t even remember why I suggested this to the board of directors. It feels like a nightmare now.)

For 60 years, Berkshire shareholders have supported the company reinvesting profits rather than dividends. This allows the company to accumulate considerable taxable income. In the first ten years, our cash income tax payments to the U.S. Treasury were negligible, but now the cumulative amount has exceeded $101 billion and is still increasing.

Such a large number may not be easy to understand. Let me talk about the $26.8 billion in 2024 in another way.

Assuming Berkshire sends a check for $1 million to the Treasury every 20 minutes throughout 2024 (366 days and 366 nights, because 2024 is a leap year), we will still owe the federal government a large amount of money by the end of the year. In fact, it was not until some time in January that the Ministry of Finance would tell us that we could rest, get some sleep, and prepare to pay the 2025 taxes.

6. Where is your money?

Berkshire’s equity investment strategy is two-pronged.

On the one hand, we control the fate of many companies and usually hold 80% or even 100% of the shares of the invested companies. We have 189 subsidiaries with a total value of hundreds of billions of dollars. Among them, there are a few high-quality companies that can be called pearls, many companies that have performed poorly and are well-behaved, and there are even some that are unsatisfactory. However, we don’t have any investment that is a burden.

On the other hand, we also hold minority stakes in some large, well-known and very profitable companies such as Apple, American Express, Coca-Cola and Moody’s. Most of these companies receive high returns on the capital they need to operate. As of the end of the year, the valuation of this stake reached US$272 billion.

Really good companies rarely sell as a whole, but their minority stakes are available every day on Wall Street, with occasional discounts.

When choosing an investment direction, we flexibly choose whether to hold a company or buy a minority stake based on where we can better use your funds (and my family’s funds). Many times, there are no particularly attractive opportunities in the market; but occasionally there are rare investment opportunities, and Greg and Charlie can make decisive moves.

In investing in listed stocks, if I make a mistake, it is relatively easy to adjust direction. But Berkshire is now too big, and this flexibility is eroded, and we can’t get in and out of the market quickly like small companies.

Sometimes, it can take more than a year to establish or divest an investment. In addition, when we only hold a minority stake, we cannot intervene directly if we are not satisfied with the company’s capital operations.

With holding companies, we can make decisions directly, but we have much less flexibility when correcting mistakes. In fact, Berkshire almost never sells a holding company unless we encounter unsolvable problems. However, there are also some business owners who actively seek cooperation because of our steady style, which is a great advantage for us.

Although Berkshire is believed to hold a lot of cash, most of your money is still invested in stocks, and this strategy will not change. Although our holdings in listed stocks fell to $272 billion from $354 billion last year, the value of our unlisted controlling equity increased slightly and far exceeded the value of our listed investment portfolio.

Berkshire shareholders can rest assured that we will always invest most of our money in stocks, mainly U.S. stocks, even though many of these companies also have important international businesses.

We prefer to invest in companies (whether controlling or holding shares) rather than holding cash. If fiscal policy gets out of control, the value of paper money may evaporate. Such reckless practices have become the norm in some countries, and there have been similar dangerous moments in the United States, where fixed-coupon bonds have no protection against runaway currencies, but companies and specific individuals, as long as their products or services are popular in the market, can often find ways to deal with currency instability.

I have relied on stocks all my life because I have no sporting talent, a wonderful singing voice, medical or legal skills, or other special talents. I rely on the success of American businesses and will continue to do so.

In any case, citizens ‘wise and imaginative use of savings is a necessary condition for the continuous growth of society. This system is called capitalism. It has shortcomings and abuses, and in some respects is even more serious than before, but it can also create miracles unmatched by other economic systems. The United States is the best example. Our country has made progress in its short 235 years of history that even the most optimistic colonists of 1789 could not have imagined. At that time, the constitution was adopted and the potential of the country was released.

In the early days of the country, we sometimes borrowed from abroad to replenish domestic savings. But at the same time, we need many Americans to continue saving, and then those savers or others use the money wisely. If the United States consumes only everything it produces, the country will stagnate.

America’s development history has not always been so beautiful. Our country has always had many scoundrels and speculators who try to take advantage of those who trust them. But even with this misconduct, Americans ‘savings still produce more output than anyone imagined.

Starting from an initial base of only four million people, despite the early outbreak of civil war and Americans confronting each other, the United States changed the world in a short period of time.

Berkshire shareholders participated in the American miracle by forgoing dividends and choosing to reinvest rather than consume. Initially, this reinvestment was trivial and almost meaningless, but over time it exploded, reflecting the magic of a continuous saving culture and long-term compound interest.

Today, Berkshire’s business has penetrated every corner of the United States, and we are not done yet. There are many reasons why companies die, but unlike the fate of humans, old age is not fatal in itself.

Berkshire is much younger today than it was in 1965.

However, as Charlie and I have always admitted, Berkshire can achieve this only in the United States, which would have achieved the same success without Berkshire.

So thank you, Uncle Sam. One day, Berkshire shareholders hope to pay you more in taxes than they did in 2024. Please use this money wisely and take care of people who have been at a disadvantage without fault in life, and they deserve better treatment.

7. Property and accident insurance

Property and casualty insurance remains Berkshire’s core business, and their financial model is quite unique: revenue comes first, costs come later.

Generally, companies incur costs such as labor, materials, inventory, plant and equipment before or at the same time as selling products or services. Therefore, the CEO of a company can actually understand the cost before selling the product. If the sales price is below the cost, managers will quickly realize the problem: cash losses are hard to ignore.

However, when underwriting property and casualty insurance, we receive premiums in advance and don’t know the cost until a long time later. Sometimes the truth can be delayed by 30 years or more. For example, we are still paying huge compensation for asbestos exposure more than 50 years ago.

One benefit of this business model is that it allows insurance companies to get cash, but there is also the risk that companies may lose revenue, sometimes huge losses, before the CEO and board realize the payout.

Certain insurance business lines are minimizing this mismatch. For example, crop insurance or hail damage, these losses are reported quickly, assessed and paid for. However, other business lines may leave company management and shareholders immersed in happiness when the company is about to go bankrupt. Examples include medical malpractice or product liability insurance.

In long-tail business lines, insurance companies can report large but false profits to their owners and regulators for years or even decades. This kind of false reporting is particularly dangerous if the CEO is an optimist or a liar, and there are already many precedents.

Over the past few decades, this collection-first, pay-later model has allowed Berkshire to invest large amounts of money (i.e. float) while generally achieving what we consider small underwriting profits. We made predictions for the accident, and so far, these estimates are sufficient.

We are not discouraged by the huge and growing payouts from the event. Our job is to set prices to absorb these losses and calmly take the blow when accidents occur, and we also oppose runaway rulings, false litigation and blatant fraud.“”

Under the leadership of Ajit, our insurance business grew from an obscure Omaha company to a world leader and is known for its appetite for risk and Gibraltar’s financial strength. In addition, Greg, our directors and I all have personal investments in Berkshire far exceed any compensation we receive.

We don’t use options or other unilateral forms of compensation: if you lose money, we lose money. This approach encourages caution but does not guarantee foresight.

Taken together, we like the property and casualty insurance business, and Berkshire can cope with extreme losses with ease, financially and psychologically. We also do not rely on reinsurers, which gives us a substantial and lasting cost advantage. Finally, we have great managers (no optimists) and are particularly good at investing large amounts of money from property and accident insurance.

Over the past two decades, our insurance business has achieved $32 billion in after-tax underwriting profits, equivalent to 3.3 cents per dollar of sales. At the same time, our float increased from $46 billion to $171 billion. Float is likely to continue to grow slightly over time, and with wise underwriting (and some luck) it is expected to achieve zero costs.

8. Will increase investment in Japan

Although Berkshire’s investment focus is mainly in North America, our investment in Japan is a small but significant exception.

Since we first purchased shares in five Japanese companies in July 2019, our investments in these companies have continued to grow. The five companies are ITOCHU, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Mitsui and Sumitomo. These companies not only have many businesses in Japan, but also have extensive deployments around the world.

We were initially attracted by the extremely low stock prices of these companies, but over time our admiration for them grew. The operating models of these five companies share many similarities to Berkshire’s, and they have performed well in capital allocation, management capabilities and attitude towards investors. They increase dividends at the right time, buy back shares reasonably, and executive compensation is far less aggressive than their American counterparts.

Our shareholding in these five companies is long-term and we are committed to supporting their boards. Initially, we agreed to limit our shareholding to less than 10% per company, but as we approached this limit, the five companies agreed to moderately relax the restrictions. In the future, Berkshire may further increase its shareholding in these five companies.

As of the end of 2024, Berkshire’s total investment costs in these five Japanese companies were US$13.8 billion, while the market value had reached US$23.5 billion. We balanced our investments through yen-denominated borrowing, a strategy that kept us roughly currency neutral.

In 2024, due to the strength of the US dollar, we received US$2.3 billion in after-tax gains from borrowing in yen, of which US$850 million occurred in 2024.

Looking forward, we expect Gregg and his successor will continue to hold these Japanese assets for decades, and Berkshire may explore more opportunities for cooperation with these five companies. We are satisfied with our current investment strategy and expect annual dividend income from these Japanese investments to reach approximately US$812 million in 2025, while interest costs on yen debt are approximately US$135 million.

Overall, Japanese investment has brought considerable returns to Berkshire and provided us with opportunities to further expand the international market.

9. 2025 Omaha Shareholders ‘Meeting

Dear shareholders, I hope you will come to Omaha on May 3 to attend our annual party. This year’s schedule has been slightly adjusted, but the core content remains the same: answer shareholders ‘questions, interact with each other, and hope you have a good experience in Omaha.

This year, we will still have a team of volunteers to serve you and provide a rich range of Berkshire products, so that you can feel our enthusiasm while shopping easily. As in previous years, the trade fair will be open from 12 noon to 5 p.m. on Friday, and will feature lovely Squishmallows plush toys, Fruit of the Loom underwear, Brooks running shoes and many more items to choose from.

This year we still only released one book,”60 Years of Berkshire Hathaway.”

In 2015, I invited Carrie Sova to write this relaxing and enjoyable Berkshire history book, which is an amazing book. This year, she produced a 60th anniversary edition of the book, which included rare photos, quotes and stories of Charlie Munger.

In addition, we have also prepared some special activities. For example, Greg and Ajit will answer your questions. We will take a half-hour break at 10:30 a.m. and continue at 11:00 a.m. until 1:00 p.m., but shopping in the exhibition area will last until 4:00 p.m.

Finally, I would like to make a special mention of my sister Bertie. She is 91 years old this year and is still in high spirits. She and her two daughters will come to the party. Bertie said that when she uses crutches, men stop courting her because men have strong self-esteem and feel that elderly women with crutches are clearly not a suitable target for them.“” However, I doubt this statement a little, and I bet she will still attract the attention of a lot of men.

All in all, Berkshire directors and I are very much looking forward to meeting you in Omaha, and I believe that you will have a great time and may make some new friends.