① On Saturday evening, Beijing time, Berkshire Hathaway released its 2024 fiscal year annual report and an annual Buffett shareholder letter;

② Buffett responded to hot issues such as a large number of cash positions and Japanese investment in his shareholder letter, and also discussed his views on various aspects such as investment and life.

Introduction: Buffett’s ten-thousand-word letter mainly contains four parts:

① Explore the philosophy of identifying and employing people through “Berkshire Historical Story”, and then introduce Berkshire’s performance last year to shareholders;

② Explain investment behaviors and concepts against the background of cash levels hitting new highs and selling U.S. stocks for nine consecutive quarters;

③ Discuss views on the Japanese market and disclose the next action plan;

④ The schedule of this year’s annual shareholders ‘meeting has been adjusted, and Buffett rarely disclosed his physical condition.

Streamlined summary: Berkshire Annual Report Buffett Shareholders ‘Letter Highlights: Cash level hits a new high,”stock god” is on crutches

The following begins with the main text

To Berkshire Hathaway shareholders:

This letter is presented to you as part of Berkshire’s annual report. As a listed company, we have the responsibility to provide you with a lot of specific data and information on a regular basis.

However, the word “report” implies greater responsibility. In addition to the required disclosure content, we believe it is necessary to provide you with additional explanations of the operating status of the assets we hold and our decision-making ideas. Our goal is to establish a role-swapping communication method-assuming you are CEO of Berkshire and my family and I are passive investors trusting you with our savings.

This approach prompts us to provide annual accounts of the good and bad things that happen in many of the businesses you indirectly own through Berkshire shares. However, when discussing specific subsidiaries, we try to follow the advice Tom Murphy gave me 60 years ago: “Give praise by name and criticize by category.”

(Note: Tom Murphy is a former Berkshire director who passed away shortly after resigning in 2022.)

Mistakes-yes, we make mistakes at Berkshire

I occasionally make mistakes when assessing the future economic prospects of acquisition targets-these are essentially capital allocation mistakes. This can happen in the judgment of both tradable stocks (which we regard as part ownership of the business) and 100% acquired equity.

At other times, I will deviate when assessing management’s capabilities or loyalty. Loyalty issues often cause more harm than financial losses and can be as painful as a broken marriage.

It is rare to maintain a high success rate in personnel decisions. The most unforgivable mistake is procrastination in correcting errors, or what Charlie Munger calls the “thumb-sucking” phenomenon. He often reminds me that problems will not disappear through fantasy and must be put into action, even if the process is uncomfortable.

2019-2023 During the year 2000, I used wrong or misguided words 16 times in my letters to you."""" Many other large companies have never used these two terms during this time. What is worthy of recognition is that Amazon showed rare candor in its 2021 letter to shareholders. Elsewhere, it’s usually a few pleasant words and pictures.

I have served as a director of many listed companies, and the use of “wrong” terms is strictly prohibited in board meetings or analyst phone meetings of these companies. This taboo, which implies the perfection of management, always makes me uneasy (although reservations are sometimes necessary for legal reasons, given that we live in a society where litigation is rife).

I am 94 years old this year, and it will not be far from the day when Greg Abel takes over as CEO and writes a shareholder letter. Greg agrees with Berkshire’s credo that “reporting” is the annual obligation of Berkshire’s CEO to shareholders. He also understands that if you start deceiving your shareholders, you will soon believe your own nonsense and eventually fall into the quagmire of self-deception.

Pete Ligel-unique

Let me stop and tell you the extraordinary story of Pete Ligel, a man whom most Berkshire shareholders didn’t know but who contributed tens of billions of dollars to Berkshire’s collective wealth. Pitt passed away in November at the age of 80 and was still working until the end of his life.

I first heard of Forest River-the company Pitt founded and managed in Indiana-on June 21, 2005. That day, I received a letter from an agency detailing relevant data for the company, a recreational vehicle manufacturer. The writer said that as the 100% owner of Forest River, Pitt was particularly interested in selling the company to Berkshire. He also told me the price Pete expected to receive. This straightforward style wins my heart.

I did some research with some recreational vehicle dealers, was satisfied with what I knew, and arranged for a meeting in Omaha on June 28. Pete arrived with his wife Sharon and daughter Lisa. When we met, Pete assured me that he wanted to continue the business, but would have no worries if he could ensure his family’s financial security.

Pitt went on to mention that he owned some real estate leased to Forest River that was not mentioned in the June 21 letter. A few minutes later, we reached an agreement on the price of these assets because I said Berkshire did not need to conduct a review and would just accept his offer.

Then we reached another critical point that needed to be clearly stated. I asked Pete what his salary should be and added that I would accept whatever price he called out (I should add that this is not an approach I recommend generally).

Pete paused, and his wife, daughter and I leaned forward. Then he surprised us: “Well, I read Berkshire’s proxy statement, and I didn’t want to make more money than my boss, so I was paid $100,000 a year.” After I recovered from the shock, he added: “But if the company’s profits exceed current levels, I ask for a bonus of 10% of the excess.” I immediately agreed to add only a clause that “appropriate adjustments to additional capital should be made in the event of a major acquisition”-the vague definitions of “appropriate” and “significant” have never been controversial.

The four of us then went to the Happy Valley Club in Omaha for dinner and lived happily ever after. Over the next 19 years, Pitt performed very well, and he created results that were beyond the reach of his competitors.

Not every company has a simple and easy-to-understand business model, and operators like Pitt are even rare. Of course, I expect to make some mistakes with the businesses Berkshire buys, and sometimes I make mistakes when evaluating the people I deal with.

But I also have many pleasant surprises about the potential of the business and the ability and loyalty of the managers. Our experience is that a successful decision can have astonishing long-term compound interest effects (think of GEICO as a business decision, Ajit Jain as a management decision, and my luck in finding Charlie Munger as a unique partner, personal consultant and staunch friend). Mistakes will eventually disappear, and the flower of victory will bloom forever.

One more point to make in our CEO selection: I never look at which school a candidate has attended. Never!

It is true that many outstanding managers come from prestigious schools, but there are not a few people like Pitt who have not completed their studies but have achieved great achievements. Look at my friend Bill Gates, who decided that getting started in an explosive industry that will change the world was more important than insisting on getting a piece of parchment to hang on the wall (recommended reading his new book,”Source Code”).

Not long ago, I met Jessica Tunkel over the phone, whose stepgrandfather Ben Rosner had run a business for Charlie and me. Ben is a retail genius. In order to prepare for this report, I checked Ben’s academic qualifications with Jessica, and I remember his academic qualifications were very limited. Jessica’s answer was: “Ben stopped at sixth grade.”

I am fortunate to receive an education at three excellent universities and am passionate about lifelong learning. However, I have observed that a large part of business talent is born, and nature overrides acquired cultivation.

Peter Ligel is a model of extraordinary talent.

last year’s performance

In 2024, Berkshire performed better than I expected, even though 53% of our 189 operating companies reported declining earnings. We have benefited from a large and predictable increase in investment income as Treasury yields have improved and we have significantly increased our holdings of these highly liquid short-term securities.

Our insurance business also achieved significant growth in earnings, mainly due to the performance of GEICO. Todd Combs spent five years strategically reshaping GEICO, improving operational efficiency and innovating the underwriting system. This established company has undergone in-depth polishing. Although it has not yet been fully transformed, the improvements in 2024 are amazing.

Overall, property and accidental injury (“P/C”) insurance pricing will strengthen in 2024, reflecting a response to intensified convective storm losses. Climate change may have announced its arrival. However, there have been no “monster” incidents during 2024. One day, any day, truly shocking insured losses can occur-and there is no guarantee that they will only occur once a year.

The P/C business is so important to Berkshire that it deserves further discussion later in this letter.

Berkshire’s rail and utility operations, the two largest businesses outside our insurance business, have increased their total earnings. However, there is still a lot of work to be done for both.

At the end of the year, we increased our shareholding in utilities from 92% to 100% at a cost of US$3.9 billion, of which US$2.9 billion was paid in cash and the rest was settled in Berkshire Class B shares.

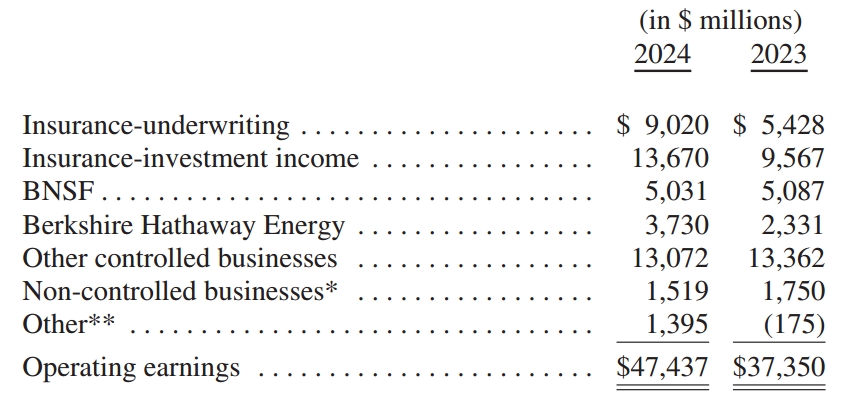

All in all, we recorded operating income of $47.4 billion in 2024. We often-and some readers may complain endlessly-emphasize this metric rather than the GAAP stated benefits in our reports.

Our measures do not include capital gains or losses on the stocks and bonds we hold, whether realized or unrealized. In the long run, we think earnings are likely to prevail-otherwise why would we buy these securities? — Although year-to-year numbers may fluctuate sharply and unpredictably. Our vision of such commitments almost always extends well beyond a year. In many cases, our thinking spans decades. These long-term investments sometimes make the cash register ring like church bells.

Here is our breakdown of 2023-24 earnings. All calculations are made after depreciation, amortization and income taxes. EBITDA, Wall Street’s favorite flawed indicator, is not for us.

(In order, insurance underwriting, insurance investment income, BNSF, Berkshire Hathaway Energy, other controlled enterprises, non-controlled enterprises *, other **, operating profit)

* Including certain companies in which Berkshire owns 20% to 50% ownership, such as Kraft Heinz, Occidental Oil and Bercadia.

** Including approximately US$1.1 billion in foreign exchange gains (2024) and approximately US$211 million in foreign exchange gains (2023) due to our use of non-dollar denominated debt.

Surprise, surprise! An important American record was broken

Sixty years ago, current management took over Berkshire. This move was a mistake–my mistake–a mistake that has troubled us for two decades. I should emphasize that Charlie immediately discovered my obvious mistake: Although the price I paid for Berkshire seemed cheap, its business-a large northern textile business-was dying.

The U.S. Treasury has already received silent warnings about Berkshire’s fate. For ten years before 1965, Berkshire paid no income tax. This may be understandable for charismatic start-ups, but when it happens in pillars of American industry, it’s a flashing yellow light. At that time, Berkshire was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Sixty years later, imagine the Treasury’s surprise when the same company-still operating under the name Berkshire Hathaway-pays much more corporate income tax than the U.S. government receives from any company, including U.S. technology giants with market capitalizations of trillions of dollars.

To be precise, Berkshire made four payments to the IRS last year, totaling $26.8 billion. That’s about 5% of what all companies in the United States pay (in addition, we pay significant income taxes to foreign governments and 44 states).

A key factor in allowing such record payments requires attention: During the period 1965-2024, Berkshire shareholders received only one cash dividend. On January 3, 1967, we made the only payment-$101,755 or 10 cents per A share (I can’t remember why I proposed this action to Berkshire’s board of directors, and now it seems like a nightmare).

Over the past 60 years, Berkshire shareholders have supported continued reinvestment, which has allowed the company to build its taxable income. Cash income taxes paid to the U.S. Treasury, which were negligible in the first decade, now total more than $101 billion… and rising.

The huge numbers may be hard to imagine. Let me restate the $26.8 billion we paid last year.

If Berkshire sent a $1 million check to the Treasury every 20 minutes throughout 2024-imagine 366 days and nights, because 2024 is a leap year-we would still owe the federal government a lot of money at the end of the year. In fact, it will not be until mid-January before the Ministry of Finance will tell us that we can take a little rest, get a good night’s sleep, and prepare for continuing to pay taxes in 2025.

Where’s your money?

Berkshire’s equity activities show two-sided flexibility. On the one hand, we control many companies and hold at least 80% of the investee shares, and usually 100% of the equity. These 189 subsidiaries have similarities to tradable common stock, but are far from identical. The collection is worth hundreds of billions of dollars and includes some rare gems, many good but far from amazing businesses, and some disappointing companies that perform poorly. We don’t have any major drag down, but there are some businesses I shouldn’t have bought.

On the other hand, we own small stakes in more than a dozen very large and lucrative companies with household names such as Apple, American Express, Coca-Cola and Moody’s. Many of these companies ‘businesses have achieved very high returns on the net tangible equity they need to operate. At the end of the year, our partial ownership stake was worth $272 billion. Understandably, truly outstanding companies rarely sell in their entirety, but small portions of these gems can be purchased on Wall Street from Monday to Friday, and very occasionally, they are sold at a discounted price.

We are impartial in selecting equity instruments and invest in either of these two types based on where we believe your (and my family) savings can best be deployed. Often, nothing seems very attractive; very rarely, we find ourselves mired in opportunities. Greg has vividly demonstrated his ability to take action at these times, just like Charlie.

With tradable stocks, it’s easier to change direction when I make a mistake. It should be emphasized that Berkshire’s current size reduces this valuable option. We cannot come and go as we please in an instant. Sometimes it takes a year or more to build or divest an investment. In addition, for minority interests, we cannot change management if action is needed, and we cannot control capital flows if we are not satisfied with the decisions made.

Although the holding company can make decisions independently, it has low flexibility to deal with mistakes. In fact, Berkshire almost never sells controlled companies unless faced with problems we believe will persist. One offsetting factor is that some business owners seek to work with Berkshire because of our unwavering behavior. This could be a clear advantage for us.

Although some commentators currently believe Berkshire’s cash position is very high, most of your money is still invested in stocks. This preference will not change. Although our ownership in tradable stocks fell from $354 billion to $272 billion last year, the value of our unlisted controlled stocks has increased and remains much greater than the value of our tradable portfolio.

Berkshire shareholders can rest assured that we will always invest most of their money in stocks-mainly U.S. stocks, although many of them will have significant international businesses. Berkshire would never prefer ownership of cash equivalent assets to owning good businesses, whether controlled or partially owned.

If fiscal stupidity prevails, paper money may see its value evaporate. In some countries, this reckless approach has become a habit, and in our country’s short history, the United States has been close to the brink. Fixed-coupon bonds are not immune to runaway currencies.

However, businesses and individuals with the necessary skills can often find a way to deal with currency instability, as long as their goods or services are popular with citizens of the country. The same goes for personal skills. Lacking assets such as sporting excellence, a beautiful voice, medical or legal skills or any special talent, I have had to rely on stocks all my life. In fact, I have always relied on the success of American companies and will continue to do so.

In any case, citizens ‘wise allocation of savings is the core driving force for the growth of social output. This system is called capitalism. It has its shortcomings and abuses-in some ways it is more serious now than ever-but it can also work unmatched miracles.

The United States is the best example. The country has made progress in just 235 years of existence far beyond the most optimistic assumptions when the Constitution was promulgated in 1789.

It is true that in its early days, the United States sometimes borrowed from abroad to replenish our own savings. But at the same time, we need many Americans to continue saving, and then we need those savers or other Americans to wisely deploy the resulting capital. If the United States consumes everything it produces, the country will stand still.

The process is not always beautiful-there will always be many scoundrels and salesmen in our country who try to take advantage of people who mistakenly entrust them with savings. But even with such misconduct-which is still common today-and the large number of capital deployments that ultimately failed due to brutal competition or disruptive innovation, American savings have provided a quantity and quality of output that exceeds the dreams of any colonizer.

Starting from a base of only 4 million people, the United States changed the world in a short period of time despite a brutal internal war in its early days that set Americans against each other.

In a very small way, Berkshire shareholders participated in the American miracle by forgoing dividends and choosing to reinvest rather than consume. Initially, this reinvestment was negligible and almost negligible, but over time it grew exponentially, reflecting a combination of a continued saving culture and long-term compound interest.

Berkshire’s activities now affect every corner of our country, and expansion and development continue. Companies die for a variety of reasons, but unlike humans, age itself is not fatal. Berkshire is younger today than it was in 1965.

However, as Charlie and I have always admitted, Berkshire will not achieve anywhere what it has achieved in the United States, and the United States will still achieve those achievements, even if Berkshire never existed.

Therefore, I would like to thank Uncle Sam. Future generations of Berkshire are willing to pay higher taxes. Please spend this money wisely. Take care of those who are living in poverty for reasons beyond their control. They deserve better treatment. Never forget that we need you to maintain a stable currency, and this requires wisdom and vigilance.

property and casualty insurance

P/C insurance remains Berkshire’s core business. The industry follows a financial model that is very rare among large companies.

Typically, companies bear costs for labor, materials, inventory, plant, equipment, etc. before or while selling their products or services. As a result, their CEO has a good understanding of the cost of a product before selling it. If the selling price is lower than its cost, managers quickly realize they have a problem. Cash losses are hard to ignore.

When we underwrite P/C insurance, we receive payments in advance and then learn much later what our product costs-sometimes this moment of truth is delayed for up to 30 years or more (we are still paying a lot for asbestos exposure 50 years ago or earlier).

This operating model has the ideal effect of bringing cash to P/C insurers before the company bears most of the expenses, but it also carries the risk that the company may be losing money-sometimes large losses-before the CEO and directors realize it.

Certain insurance lines can minimize this mismatch, such as crop insurance or hail damage insurance, where losses are quickly reported, assessed and paid. However, other insurance wires could lead companies to bankruptcy while executives and shareholders were happy. Examples include medical malpractice or product liability insurance. In the “long tail” insurance line, P/C insurance companies may report large but false profits to their owners and regulators for years-even decades. This accounting treatment can be particularly dangerous if the CEO is an optimist or a liar. These possibilities are not imaginary: history shows that there are many examples of every situation.

In recent decades, this “collect first, pay later” model has allowed Berkshire to invest large amounts of money (“float”) while often achieving what we consider small underwriting profits. We made estimates of the “surprises” and so far, these estimates are sufficient.

We are not intimidated by the drama and growing loss payments suffered by our activities (think of wildfires as I write this). It’s our job to endure these losses and accept the pain with a calm attitude when surprises arise. It is our job, too, to challenge “out of control” judgments, false litigation and blatant fraud.

Under Ajit’s leadership, our insurance business has grown from an unknown Omaha company to a global giant, known for its risk tolerance and financial strength. In addition, Greg, our directors and I all have very large investments in Berkshire compared to salary. We don’t use options or other unilateral forms of compensation; if you lose money, we will lose money. This approach encourages caution but does not guarantee foresight.

The growth of P/C insurance depends on the increase in economic risks. Without risk, insurance is not needed.

Recall that just 135 years ago, there were no cars, trucks or planes in the world. There are now 300 million vehicles in the United States alone, and this huge fleet causes tremendous damage every day. Property damage caused by hurricanes, tornadoes and wildfires is huge, growing, and it is increasingly difficult to predict its patterns and ultimate costs.

Underwriting these insurances for ten years would be foolish-it would be crazy-but we believe that a one-year risk-taking is usually manageable. If we change our mind, we will change the contract we offer. In my life, auto insurance companies have generally abandoned one-year policies in favor of six-month policies. The change reduces float but allows for smarter underwriting.

No private insurance company is willing to take on the amount of risk Berkshire can provide. Sometimes, this advantage can be important. But we also need to shrink when prices are insufficient. We must not insure underpriced policies in order to remain competitive. This is suicide.

Properly pricing P/C insurance is an art and a science, and it is definitely not the business of optimists. Mike Goldberg, the Berkshire executive who recruited Ajit, put it best: “Make the underwriters nervous when they work every day, but don’t be too scared to move.”

All factors taken into account, we like the P/C insurance business. Berkshire is able to manage extreme losses financially and psychologically. We also do not rely on reinsurers, which gives us a significant and lasting cost advantage. Finally, we have outstanding managers (not optimists) and are particularly well suited to investing with the large amount of money provided by P/C insurance.

Over the past two decades, the property insurance business has generated a cumulative after-tax underwriting profit of US$32 billion (equivalent to 3.3% of premium income), and floating deposits have increased from US$46 billion to US$171 billion. Float may grow slightly over time, and with smart underwriting (and some luck), there is a reasonable prospect of zero-cost use.

Berkshire increases its investment in Japan

Our investment in Japan is a small but important exception to the American-based strategy.

Since Berkshire began buying shares in five Japanese companies about six years ago, the companies have operated very successfully in a way somewhat similar to Berkshire itself. The five companies are: Itochu Corporation, Marubeni, Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsui Corporation and Sumitomo Corporation. Each of these large companies has a variety of businesses. Many of these businesses are based in Japan, and many are operated globally.

Berkshire purchased shares of these five companies for the first time in July 2019. We just looked at their financial records and were surprised at how low their stock prices were. Over time, our admiration for these companies continues to grow. Greg met with them many times, and I regularly followed their progress. We both like their capital allocation, management and attitude towards investors.

These five companies increase dividends when appropriate and buy back their own shares when reasonable, and their executives are far less aggressive in their pay plans than their U.S. counterparts.

Our shareholding in these five companies is long-term and we are committed to supporting their boards of directors. Initially, we agreed to keep Berkshire’s stake below 10% of each company’s shares. But as we approached the limit, the five companies agreed to moderately relax the cap. Over time, you may see Berkshire’s shareholding in all five companies increase slightly.

At the end of the year, Berkshire’s total investment costs in these five companies (in dollar terms) were $13.8 billion, and the market value of our shareholding totaled $23.5 billion.

At the same time, Berkshire has continued to increase its yen-denominated borrowings, but has not followed any paradigm. The interest rate on all borrowings is fixed and there is no “floating interest rate”. Greg and I have no opinion on future foreign exchange rates, so we seek a position close to currency neutrality. However, under GAAP rules, we must regularly recognize in our earnings a calculation of any gain or loss on the yen we borrowed, and at the end of the year, we included $2.3 billion in after-tax gains due to a stronger dollar, of which $850 million occurred in 2024.

I expect Greg and his successor will hold this Japanese position for decades, and Berkshire will find other ways to work with these five companies in the future.

We like the current yen balance strategy. As I write this, dividend income from Japanese investments is expected to total approximately $812 million in 2025, while interest on our yen-denominated debt will be approximately $135 million.

Annual party in Omaha

I hope you will join us for a party in Omaha on May 3rd. This year we will follow a slightly changed timetable, but the basics remain the same. Our goal is to answer many of your questions, connect you with friends, and make a good impression of Omaha. The city looks forward to your visit.

We will have a group of volunteers offering you a variety of Berkshire products that will lighten your wallet and light up your day. As always, we will be open from noon to 5 p.m. on Fridays, offering cute Squishmallows dolls, underwear from Fruit of the Loom, Brooks running shoes and a variety of other items to tempt you.

We will only sell one book again. Last year, our Poor Charlie’s Book sold out like a hit-5000 books disappeared before business closed on Saturday.

This year we will be offering 60 Years of Berkshire Hathaway. In 2015, I asked Carrie Sova (who, among many other responsibilities, manages most of the annual meeting) to try to write a light history book about Berkshire. I gave her full freedom to use her imagination, and she quickly surprised me with her originality, content and design.

Carrie then left Berkshire to start a family, and she now has three children. But every summer, Berkshire office staff gather to watch an Omaha Storm Chasers baseball game. I would invite some old colleagues to join us, and Carrie would usually come with her family. For this year’s shareholder meeting, I ventured to ask if she could make a 60th anniversary edition featuring Charlie’s photos, quotes and stories that had rarely been made public before.

Even if she had to take care of three children, Carrie immediately agreed. As a result, we will have 5000 new books available for sale on Friday afternoon and Saturday from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Carrie refused to receive any remuneration for the extensive work she did in the new edition of “Charlie”. I suggested that she and I co-sign 20 books to provide to any shareholder who donated $5000 to the Stephen Center in South Omaha, which serves homeless adults and children. The Kizel family, starting with Bill Kizel (my long-time friend and Carrie’s maternal grandfather), has been helping this valuable institution for decades. No matter how much money I raise by selling 20 signed books, I will match the same amount.

Becky Quick will cover on our redesigned party on Saturday. Becky knew Berkshire well and always arranged interesting interviews with managers, investors, shareholders and occasionally celebrities. She and her CNBC team did a great job in disseminating our meetings around the world and archiving a large amount of Berkshire related material. Our director Steve Burke should be commended for this archival idea.

This year we will not show movies, but will start early at 8 a.m. I’ll make some opening remarks, and then we’ll go straight to the Q & A session, alternating asking questions, with Becky and the audience asking questions.

Greg and Ajit will answer questions with me, and we will take a half-hour break at 10:30 a.m. When we start again at 11:00 a.m., only Greg will be on stage with me. This year we will finish at 1:00 p.m., but the exhibition area will remain open for shopping until 4:00 p.m.

You can find all the details about weekend activities on page 16. Please pay special attention to the always-popular Brooks Run, which will be held on Sunday morning (when I will be sleeping).

My smart and beautiful sister Bertie (whom I wrote about last year) will attend the meeting, accompanied by her two daughters, both of whom are also very good-looking. Observers agree that the genes that produce these dazzling results flow only on the female side of our family (Buffett: Woo…).

Bertie is now 91 years old, and we regularly talk on the old-fashioned phone on Sundays. We talked about the joys of old age and discussed exciting topics such as the relative merits of our walking sticks. For me, this effect is limited to avoiding face-down falls.

But Bertie often outdid me by asserting that she enjoyed added benefits: She told me that when a woman uses a cane, men stop “accosted” her. Bertie’s explanation is that men are so self-aware that little old ladies using canes are simply not suitable targets. Currently, I have no data to refute her assertion.

But I have doubts. At meetings, I couldn’t see very clearly from the stage, and I wanted attendees to pay attention to Bertie. Please let me know if the cane is really working. I bet she’ll be surrounded by men. For those reaching a certain age, the scene will bring back memories of Scarlett O’Hara and her hordes of male admirers in “Gone with the Wind”.

Berkshire directors and I have enjoyed your time in Omaha very much, and I predict that you will have a great time and may make some new friends.

February 22, 2025

Warren E. Buffett

Chairman of the Board